|

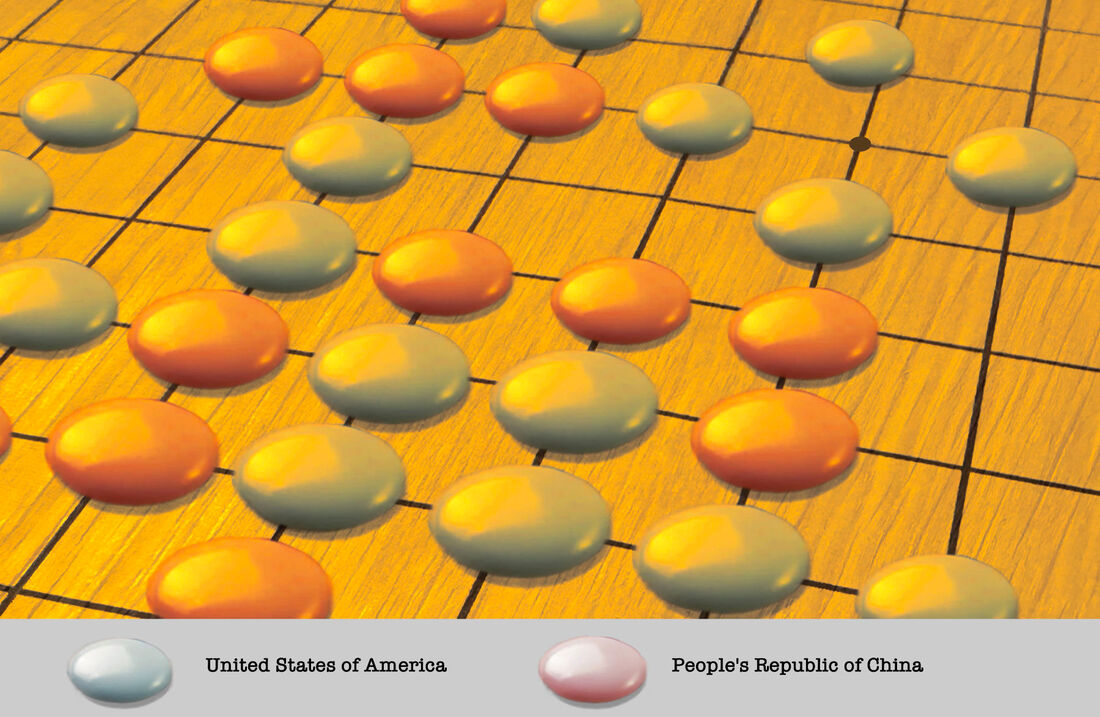

Making sure that the U.S. stays ahead

In September National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan emphasised that the U.S. had to protect the U.S.’s technology advantage. Apparently not only by outcompeting anyone else, but also by attempts to throttle key technological development in China. Sullivan argued that maintaining “relative” advantages over competitors in certain key technologies was no longer enough … Given the foundational nature of certain technologies, such as advanced logic and memory chips, we must maintain as large of a lead as possible.” In order to maintain the lead over competitors (read China) the U.S. must restrict outbound investments in sensitive technologies, “particularly investments that would not be captured by export controls and could enhance the technological capabilities of our competitors in the most sensitive areas.” (Sullivan). The two goals then for U.S.: Stay ahead in technology and prevent China from ever getting too close to overtaking the U.S. With the CHIPS ACT from august 2022 Congress and the Biden administration were trying primarily to support the first goal. The $52.7 billion CHIPS Act seeks to alleviate chips shortage and re-establish the production of advanced microchips in the U.S. In effect an attempt to bring home at least part of the fabrication of advanced semiconductor chips, presently mostly located in Taiwan. In a previous essay “The US-China war on chips” we also looked at the U.S. attempt to support the second gaol with U.S. attempts to throw a spanner into the works for China by introducing new export controls. On August 12 the U.S. established export controls on technologies that enable semiconductors, engines and power systems “to operate faster, more efficiently, longer, and in more severe conditions in both the commercial and military context” (BIS, Bureau of Industry and Security). Now the U.S. is following up with further attempts to make sure that China stays behind in the war on chips. Preventing China from ever catching up A key priority is to establish an export control system capable of throttling the Chinese military’s access to advanced AI chips. On October 7 the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) announced a new set of export controls on advanced computing and semiconductor items to China. The new BIS export controls contain two rules. The first one is meant to make sure that China cannot get access to the most advanced U.S. chips and tools used to develop and construct supercomputers, artificial intelligence applications, and manufacture advanced semiconductors. Taking the example of supercomputers the race is already on today China is competing at eyelevel with U.S. in the super computer race. Both having built supercomputers with peak performances in the ExaFLOP range. While the U.S. Frontier supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory is said to be capable of 1.5 ExaFLOPS, the Chinese Sunway Oceanlite computer is reported to have a peak performance of 1.3 exaFLOPS in 2022. (ExaFLOPS, a measure of performance for a supercomputer that can calculate at least one quintillion floating point operations per second). The Oceanlite supercomputer “is already in use and plays a starring role in a recent project designed to approach brain-scale AI where the number of parameters is similar to the number of synapses in the human brain. In fact, the project is the first to target training brain-scale models on an entire exascale supercomputer, revealing the full potential of the machine.” (asianscientist.com). There is fear such capabilities might be used by China “to produce advanced military systems including weapons of mass destruction; improve the speed and accuracy of its military decision making, planning, and logistics, as well as of its autonomous military systems; and commit human rights abuses.” Here we see a new argument creeping in, that preventing China from getting access to advanced chips and tools is also meant to prevent human rights abuses. Like surveillance capabilities to monitor own citizens. In other words: “Our actions will protect U.S. national security and foreign policy interests while also sending a clear message that U.S. technological leadership is about values as well as innovation.” (Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Export Administration). An argument to somehow elevate the U.S. attempt to keep China behind in the supercomputer race from just being concerned with technology to the noble goal of preserving and strengthening Western values. The new restrictions announced in the BIS statement adds new license requirements for items destined to be used in semiconductor fabrication. “The new rules are comprehensive, and cover a range of advanced semiconductor technology, from chips produced by the likes of AMD and Nvidia to the expensive, complex equipment needed to make those chips. Much of highest-quality chip manufacturing equipment is made by three U.S. companies: KLA, Applied Materials, and Lam Research, and cutting off China’s access to their tools has the potential to damage the country’s ambitions to become a chipmaking powerhouse.” (protocol.com). The stringent new restrictions The new restrictions for export to China announced by BIS October 7 include: Logic chips with non-planar transistor architectures (I.e., FinFET or GAAFET) of 16nm or 14nm, or below; DRAM memory chips of 18nm half-pitch or less; NAND flash memory chips with 128 layers or more. (These restrictions are meant to make sure that China will not have access to the most advanced chips, forcing China to use older designs and technologies, but it may prove impossible as SMIC, the largest chipmaker in China, is already able to produce chips with a 7nm process). Restricts the ability of U.S. persons to support the development, or production, of ICs at certain China-located semiconductor fabrication “facilities” without a license (Meaning that U.S. citizens supporting or servicing development and production of ICs in China will have to cease their work); Adds new license requirements to export items to develop or produce semiconductor manufacturing equipment and related items (restricting the export of tools that would allow China to make advanced semiconductors); and Establishes a Temporary General License (TGL) to minimize the short-term impact on the semiconductor supply chain by allowing specific, limited manufacturing activities related to items destined for use outside the PRC. (Presumable in order make sure that the new rules will not harm the U.S. itself). The second rule in in the BIS announcement is meant to make sure that Chinese and other foreign countries and companies will be added to an export black list, known as the “Entity List,” if they do not comply with the U.S. export controls. “The rule provides an example that stipulates that sustained lack of cooperation by a foreign government that prevents BIS from verifying the bona fides of companies on the Unverified List (UVL) can result in those parties being moved to the Entity List, if an end-use check is not timely scheduled and completed.” (BIS). On October 7 a total of 31 new entities were added to the list. Among those were China's top memory chipmaker YMTC (Yangtze Memory Technologies) and 30 other Chinese entities. Hurting Apple’s plans to use YMTC’s NAND flash memory chips, with Nikkei reporting that Apple has now put plans on hold. According to a BIS document 600 Chinese companies had already been added to the list. More than 110 of these since the start of the Biden presidency. Chinese reactions to US’s export ban “Full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” The quote from Shakespeare’s Macbeth may characterize the public reactions from China. And what else can they do publicly? When the CHIPS act was signed Wang Wenbin, Chinese Foreign ministry spokesperson, slammed the Act: “How the US grow its industry is its own business, but it should not set obstacles for normal economic, trade, scientific and technological exchanges and cooperation between China and the US, let alone undermine China's legitimate development rights and interests.” (Global Times). The new October restrictions were met with renewed fury. The U.S. restrictions on exports to China were seen as attempt to create a U.S. technological hegemony: “Mao Ning, a spokeswoman for the Foreign Ministry, said on Saturday that the US' new restrictions will hinder international tech exchanges and economic cooperation, and undermine the stability of global industrial and supply chains and the recovery of the world economy. The US' politicization and weaponization of technology, economic and trade issues will not stop China's development, and will only hurt the US itself, Mao added.” (People’s Daily). Global Times warns that the U.S. chips export ban “could risk as much as 30% of some global chips giants’ revenue” and harm the U.S. itself. “As it costs vast financial and human resources investment in the R&D of cutting-edge chips, US companies will unlikely see much returns without chip exports to China and could barely re-invest in future R&D,” (Gao Lingyun quoted in Global Times). Erecting barriers to trade shift production away from the countries with most efficient production, and lead to a decrease in economic growth. A recent WTO working paper that tries to model the impact of ongoing geopolitical conflicts on trade growth and innovation indicate that “welfare losses for the global economy of a decoupling scenario can be drastic, as large as 12% in some regions and larges in the lower income regions” (wto-library.org). What the U.S. may also have forgotten in their eagerness to prevent China from ever getting too close to overtaking the U.S. is that export controls may not nearly be enough. In an earlier essay “The US-China war on chips” we refer to the historical example of America colonies (later the U.S.) overtaking Britain in industrial textile manufacturing as an example showing that it might be impossible to throttle a competitor with enough human and material resources, and China certainly has the manpower and the financial resources to achieve something similar.. Mathieu Duchatel at the Institute Montaigne argues in a similar vein, when saying: The most difficult challenge for an effective chokepoint policy is intangible technology transfers through education and research cooperation, and talent recruitment. Frontal breakthroughs that would suddenly remove chokepoints seem unlikely in the medium term, but Chinese breakthroughs may happen in other innovative segments of the semiconductor industry, such as new materials and heterogeneous integration.” The fallout hitting South Korea and Taiwan October 10 South Korea published an assessment of possible consequences of the U.S. chip export ban. While it concluded that the effects should be limited it also acknowledged that the South Korean giants in the production of memory chips Samsung and Hynix and important activities in China would certainly have to take account of the new U.S. export controls. Restricting their ability to introduce more advanced technology in their memory chip fabrication in China. Earlier in the year the Taiwan chip giant TSMC stopped supplying the Chinese company Tianjin Phytium Information Technology Company with advanced chips after Phytium had been placed on the U.S. entity list, presumably as a consequence of Phytium having designed a supercomputer, which according to Datacenter Dynamics is used to simulate the performance of the new Chinese hypersonic DF-17 missile. A missile that certainly poses a new big challenge to the U.S. The possible self-harm for U.S. companies In the Chinese reaction to the U.S. export ban they warned that it would harm U.S. companies in the semiconductor sector as their involvement in China and their large export to China would be harmed. This certainly seem to be the case when noting what has happened to the share price of the companies in this sector. Asia Times on October 17 showed the decline from 52 weeks highs to 52 weeks lows: Intel (INTC) was down 56%; Micron (MU) was down 50%; Nvidia (NVDA) was down 69% (its products having been directly targeted by the Biden administration); and AMD (AMD) (also directly targeted) was down 67%. Among the companies making equipment critical for chips design and fabrication: "Applied Materials (AMAT) was down 57%; "Lam Research (LRCX) was down 59%; and "KLA (KLAC) was down 45%. Yes, there might be other factors involved in the decline, but on October 10 Applied Materials has said that the U.S. ban would reduce fourth quarter net sales by about $400 million, thus lowering profit expectations. Retaliatory measures from China might further reduce sales from these and other companies having a substantial export to China. This would mean that the Biden administration’s ban would harm not only Chinese but also American companies. The warning from history Here it may be relevant to refer back the conclusion in the earlier essay “The US-China war on chips” China may not yet a champion in the production of advanced semiconductors, but then we have to remember that Taiwan is, and China insists that there is only one China and Taiwan is part of it. And if that also became the reality, China would jump to the front in the production of advanced semiconductors. Production that is, not yet design. But China might be on the verge of overtaking the U.S. in areas related to Artificial Intelligence or AI. A final report on AI from the U.S. National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (NSCAI) published in 2021 concludes: “The leading indexes that measure progress in AI development generally place the United States ahead of China. However, the gap is closing quickly. China stands a reasonable chance of overtaking the United States as the leading center of AI innovation in the coming decade. In recent years, technology firms in China have produced pathfinding advances in natural language processing, facial recognition technology, and other AI-enabled domains.” Does history repeat itself? Not one to one of course. We are no longer talking textile machinery, but advanced semiconductors and AI. Looking at the data we have shown that it certainly seems probable that in the war on chips China might overtake the U.S. and thus the West. The present U.S. sanctions restrictions may hamper Chinese development in these areas, but also encourage Chinese to search for ways to leapfrog the U.S. based on their own efforts. Like the British attempts to prevent the growth of textile manufacturing in the colonial US and later in India, it may prove impossible to stop the colossal Chinese momentum, in research, investment and production. The U.S. realization that China might soon overtake the U.S. in AI may represent the writing on the great wall. A kind of mene mene tekel upharsin for the West. |

Author

Verner C. Petersen Archives

May 2024

|