|

Perhaps a too late to ask this question today, when Putin have decided to invade at least part of Ukraine, but it may still be relevant to look at the question in order to understand his reason for doing so.

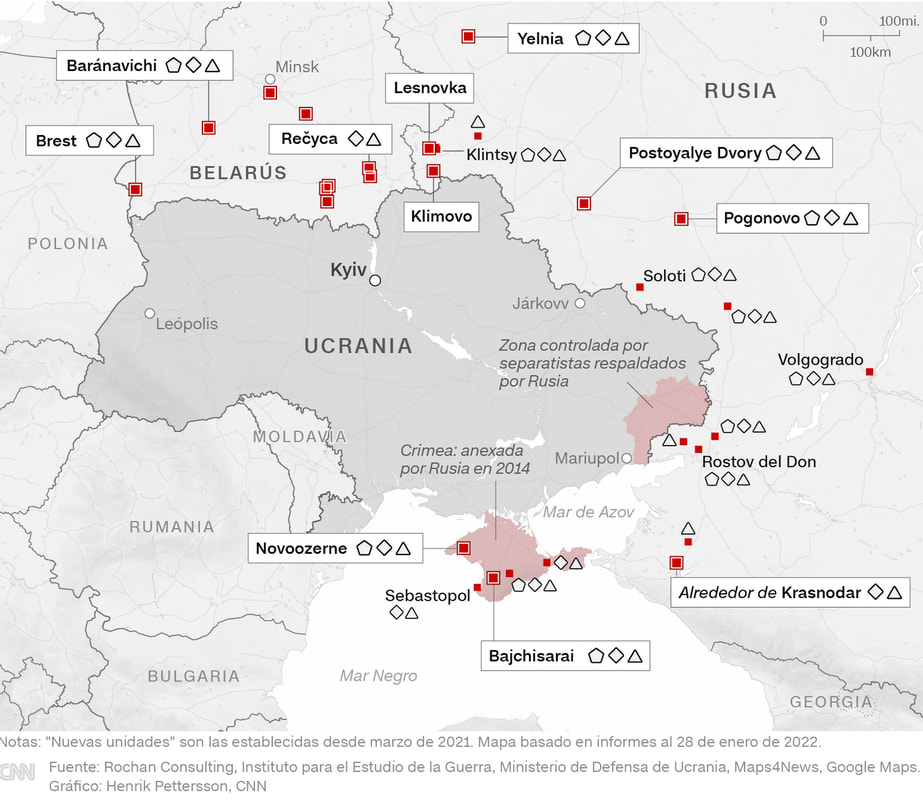

Reactions to Putin’s long speech Monday night Putin’s speech was met with reactions that can only be characterised as demeaning. “It was a messy, incoherent, angry rant that is difficult to make sense of but that put forward a dark vision of renewed national glory. Putin’s mix of half-truths, fantasies, and lies of omission rightly has neighboring states, once victims of Russian imperialism themselves, highly worried.” (foreignpolicy.com) A French official described the address to the nation by Mr Putin on Ukraine as "paranoid", accusing him of breaking promises made to his French counterpart Mr Macron (Quoted in The Telegraph). Vladimir Putin’s address to the nation on Monday was condemned as “delusional”, “insane” and “unhinged” (The Independent) Es ist eine düstere Ansprache… Es wirkt wie eine Kriegserklärung - auch an den Westen (Der Tagesspiegel). “Putin wirkt paranoid.” (Handelsblatt) Instead of doubting the mental health of Putin, one should take a closer look at what he said. Especially the words and the arguments brought up in relation to NATO’s eastward expansion. Then taking a closer look at what decisionmakers in the West hoped to achieve with the “Open Door” invitation to NATO membership for countries bordering Russia. And finally remembering that there were serious voices warning against such a policy and its consequences. Warnings that seem almost prophetical, when looking at Putin’s present attitude towards NATO. Putin’s grievances with respect to NATO “Why? What is all this about, what is the purpose? All right, you do not want to see us as friends or allies, but why make us an enemy?” (Putin, speech). In his speech on Russian on February 21 Putin explained his grievances with the NATO expansion towards the East and especially the possibility of Ukraine joining NATO: “Let me remind you that at the Bucharest NATO summit held in April 2008, the United States pushed through a decision to the effect that Ukraine and, by the way, Georgia would become NATO members. Many European allies of the United States were well aware of the risks associated with this prospect already then, but were forced to put up with the will of their senior partner. The Americans simply used them to carry out a clearly anti-Russian policy … All the while, they are trying to convince us over and over again that NATO is a peace-loving and purely defensive alliance that poses no threat to Russia. Again, they want us to take their word for it. But we are well aware of the real value of these words. In 1990, when German unification was discussed, the United States promised the Soviet leadership that NATO jurisdiction or military presence will not expand one inch to the east and that the unification of Germany will not lead to the spread of NATO's military organisation to the east. This is a quote. They issued lots of verbal assurances, all of which turned out to be empty phrases. Later, they began to assure us that the accession to NATO by Central and Eastern European countries would only improve relations with Moscow, relieve these countries of the fears steeped in their bitter historical legacy, and even create a belt of countries that are friendly towards Russia. However, the exact opposite happened. The governments of certain Eastern European countries, speculating on Russophobia, brought their complexes and stereotypes about the Russian threat to the Alliance and insisted on building up the collective defence potentials and deploying them primarily against Russia. Worse still, that happened in the 1990s and the early 2000s when, thanks to our openness and goodwill, relations between Russia and the West had reached a high level.” (en.kremlin.ru) http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/67828 “Today, one glance at the map is enough to see to what extent Western countries have kept their promise to refrain from NATO’s eastward expansion. They just cheated. We have seen five waves of NATO expansion, one after another – Poland, the Czech Republic and Hungary were admitted in 1999; Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia in 2004; Albania and Croatia in 2009; Montenegro in 2017; and North Macedonia in 2020. As a result, the Alliance, its military infrastructure has reached Russia’s borders. This is one of the key causes of the European security crisis; it has had the most negative impact on the entire system of international relations and led to the loss of mutual trust. He talked at length about the threat to Russia and provided a detailed listing of Western weapons systems and their possibilities in relation to Russia.” (en.kremlin.ru) In the speech Putin also revealed that he had asked the outgoing President Clinton how he would feel about admitting Russia to NATO. “The reaction to my question was, let us say, quite restrained, and the Americans’ true attitude to that possibility can actually be seen from their subsequent steps with regard to our country.” (en.kremlin.ru) Putin argued that Russia had even proposed New European Security Treaty, which might have help solve the Russian grievances, but was rejected by the West. “We are well aware of our enormous responsibility when it comes to regional and global stability. Back in 2008, Russia put forth an initiative to conclude a European Security Treaty under which not a single Euro-Atlantic state or international organisation could strengthen their security at the expense of the security of others. However, our proposal was rejected right off the bat on the pretext that Russia should not be allowed to put limits on NATO activities.” (en.kremlin.ru) The recent demands on the U.S. and NATO These grievances and the possibility of Ukraine joining NATO may explain why Russia handed the U.S. and NATO a draft for treaty on security guarantees, containing three key demands: “First, to prevent further NATO expansion. Second, to have the Alliance refrain from deploying assault weapon systems on Russian borders. And finally, rolling back the bloc's military capability and infrastructure in Europe to where they were in 1997, when the NATO-Russia Founding Act was signed.” (en.kremlin.ru) The written answers from the U.S. and NATO in gave no indications that Russia’s demands would be taken seriously, causing a visibly angry Putin to state: “I would like to be clear and straightforward: in the current circumstances, when our proposals for an equal dialogue on fundamental issues have actually remained unanswered by the United States and NATO, when the level of threats to our country has increased significantly, Russia has every right to respond in order to ensure its security. That is exactly what we will do.” (en.kremlin.ru) That Monday evening February 21 he concluded his speech by announcing: “I consider it necessary to take a long overdue decision and to immediately recognise the independence and sovereignty of the Donetsk People's Republic and the Lugansk People's Republic. I would like to ask the Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation to support this decision and then ratify the Treaty of Friendship and Mutual Assistance with both republics. These two documents will be prepared and signed shortly.” (en.kremlin.ru). The once optimistic American view of NATO’s expansion eastwards When President Clinton in 1997 gave a commencement address at the United States Military Academy at West Point, he presented an optimistic view of a new NATO and invited new countries in Central Europe to join the alliance: “To build and secure a new Europe, peaceful, democratic, and undivided at last, there must be a new NATO, with new missions, new members, and new partners. We have been building that kind of NATO for the last 3 years with new partners in the Partnership for Peace and NATO's first out-of-area mission in Bosnia. In Paris last week, we took another giant stride forward when Russia entered a new partnership with NATO, choosing cooperation over confrontation, as both sides affirmed that the world is different now. European security is no longer a zero-sum contest between Russia and NATO but a cherished common goal. In a little more than a month, I will join with other NATO leaders in Madrid to invite the first of Europe's new democracies in Central Europe to join our alliance, with the consent of the Senate, by 1999, the 50th anniversary of NATO's founding.” (presidency.ucsb.edu). https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/commencement-address-the-united-states-military-academy-west-point-new-york-0 “Some say we no longer need NATO because there is no powerful threat to our security now. I say there is no powerful threat in part because NATO is there. And enlargement will help make it stronger. I believe we should take in new members to NATO for four reasons. First, it will strengthen our alliance in meeting the security challenges of the 21st century, addressing conflicts that threaten the common peace of all. Consider Bosnia. Second, NATO enlargement will help to secure the historic gains of democracy in Europe … the opening of NATO's doors has led the Central European nations already—already—to deepen democratic reform, to strengthen civilian control of their military, to open their economies. Membership and its future prospect will give them the confidence to stay the course. Third, enlarging NATO will encourage prospective members to resolve their differences peacefully. Fourth, enlarging NATO, along with its Partnership For Peace with many other nations and its special agreement with Russia and its soon to-be-signed partnership with Ukraine, will erase the artificial line in Europe that Stalin drew and bring Europe together in security, not keep it apart in instability.” (Clinton Address 1997). Biden: “50 years of peace” When the U.S. Senate in 1998 overwhelmingly approved the eastward expansion of NATO to include Poland, Hungary and the Czech, the Republic Senator Joseph R. Biden Jr. said: “…this, in fact, is the beginning of another 50 years of peace, … "In a larger sense," he added, "we'll be righting an historical injustice forced upon the Poles, Czechs and Hungarians by Joseph Stalin." (washingtonpost.com) https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1998/05/01/senate-approves-expansion-of-nato/38dded71-978c-475a-8852-58f5e285e572/ Joe Biden was at that time a key advocate for The NATO expansion in the Foreign Relations Committee. Well, today it seems that peace may not last that long, but it may perhaps explain why Biden is so stubborn in his present rejection of the Russian view. Hallelujah Clinton’s optimistic vision was also shared by Secretary of State, Albright. When the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland joined NATO on March 12, 1999 she exclaimed “Hallelujah.” She added: “To them I say that President Clinton's pledge is now fulfilled. Never again will your ates be tossed around like poker chips on a bargaining table. Whether you are helping to revise the Alliance's strategic concept or engaging in NATO's partnership with Russia, the promise of "nothing about you without you," is now formalized. You are truly allies; you are truly home … For NATO's purpose is not to build new walls, but rather to tear old walls down.” https://1997-2001.state.gov/www/statements/1999/990312.html Was NATO’s eager expansion a serious mistake? Before the 1998 Senate vote on NATO’s expansion, there had a discussion where dissenting voices were heard. Democratic senator Patrick Moynihan, warned that NATO expansion into the former Soviet bloc would exacerbate tensions with a weakened but still nuclear-armed Russia and risk a revival of Cold War tensions. "Back to the hair trigger," (Washingtonpost.com) Republican senator Robert Smith followed up by saying that it would stoke fires of anti-Western nationalism and undermine democratic forces in Russia. “A fateful error” This is what George F. Kennan, the influential American diplomat and historian, called the idea that it had somehow and somewhere been decided to expand NATO up to Russia's borders. George Kennan certainly knew something about Russia and its relations with West. He was the author of the famous “Long Telegram” sent from Moscow to the State Department in 1946, while he was charge d’affaires in Moscow. This telegram is said to have initiated the containment strategy that characterised America’s relation to USSR for a long time. The lengthy memorandum began with the assertion that the Soviet Union could not foresee “permanent peaceful coexistence” with the West. This “neurotic view of world affairs” was a manifestation of the “instinctive Russian sense of insecurity.” After the fall of communist Russia, he apparently had his eye on very different strategy in relation to new Russia. A new strategy aiming for some form of cooperation with Russia. Something that he feared would impossible with NATO’s expansion to Russia’s border. “…perhaps it is not too late to advance a view that, I believe, is not only mine alone but is shared by a number of others with extensive and in most instances more recent experience in Russian matters. The view, bluntly stated, is that expanding NATO would be the most fateful error of American policy in the entire post-cold-war era. Such a decision may be expected to inflame the nationalistic, anti-Western and militaristic tendencies in Russian opinion; to have an adverse effect on the development of Russian democracy; to restore the atmosphere of the cold war to East-West relations, and to impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking.” (NYT 1996). https://www.nytimes.com/1997/02/05/opinion/a-fateful-error.html Wise words in 1996, before the actual decision to expand NATO, and in some sense prescient with regard to the Russia’s reactions, once it had got some kind of hold upon itself in the wake of the dissolution of the USSR. Perhaps we may even use the phrases from the long telegram. How a Russian reaction to NATO’s expansion might provoke “an instinctive Russian sense of insecurity.” At a debate on NATO enlargement before the Committee on Foreign Relations in November 1997, Admiral Shanahan USN (ret,) Director of the Center for Defense Information presented a similar view: “I oppose NATO expansion on the grounds that we are sacrificing our long-term relations with Russia on the altar of an ill-conceived plan to haphazardly expand an outmoded military alliance, ill conceived for domestic political purposes, ill conceived as a legacy for one man, and ill conceived since we are not clear on why, how, when, and where to expand… It is haphazard because we don't know how many countries will eventually join. There is no clear definition of NATO's new mission and there is no clear idea of the real costs… That concern has to do with the need to maintain our bilateral relations with Russia, which are more important to the long-term security and economic interests of the United States and the American people and which far outweigh the fuzzy goals of NATO expansion out there on which Russian cooperation is essential. (govinfo.gov).” https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-105shrg46832/html/CHRG-105shrg46832.htm NATO 2030 – Report from reflection group On 25 November 2020 NATO published “NATO 2030: United for New Era,” containing the analysis and recommendations of the reflection group appointed by Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg. The reflection group behind NATO-2030 finds a long list existing and foreseeable future challenges and threats, here especially Russia “In the Euro-Atlantic area, the most profound geopolitical challenge is posed by Russia. While Russia is by economic and social measures a declining power, it has proven itself capable of territorial aggression and is likely to remain a chief threat facing NATO over the coming decade. Russia maintains a powerful conventional military and robust nuclear arsenal that poses a threat across NATO territory, but is particularly acute on the eastern flank. ...Russia also threatens NATO in non-kinetic domains in ways that blur the lines between war and peace.” (NATO-2030). In the somewhat Eurocentric view of the reflection group, is apparently still seen as the dominant threat to the West. The group continue to see Russia as a main adversary, so nothing really new here. The reflection group really doesn’t have any new ideas of how to cope with the potential Russian threats. They in fact recommend the continuation of the age-old dual-track approach of deterrence and dialogue. Neither of which really seems to have worked very well in relation to Russian activities in the recent years. “The Alliance should consider a dynamic template under which it takes steps to raise the costs for Russian aggression (e.g., coordinating to tighten rather than merely renew sanctions, according to Russian behaviour, exposing the facts of Russian covert activities in Ukraine, etc.) while at the same time supporting increased political outreach to negotiate arms control and risk reduction measures.” (NATO-2030). Nothing really new and nothing that seems to have worked very well in the recent years. The carrot and stick approach further weakened by the bickering among the NATO Allies. The analyses and recommendations in “NATO-2030” presents neither a complete overview of the challenges, nor do they present new answers to Russian challenges. Instead, we find wishful thinking and unfounded hopes based to upon an approach that hasn’t worked. What could be done instead? Macron and Trump have both spoken in favour of a better relationship with Russia. Perhaps Trump’s negative view of NATO (up to a point) and his idea of working for better relations with Russia would even have prevented the present mess of threats, counter threats and a Ukraine invasion. The EU ought to have even greater interest in a good relationship with Russia. In the medium and long term, the threat to NATO and the West will not come from Russia, but from a very self-conscious and very strong China, a troubled Middle East, and a perhaps completely ungovernable Africa with a huge population surplus. Sooner or later the West may find that Russia will have to become an essential partner for the West in what may very soon become a hegemonic struggle in the bi-polar world of Chinese hegemony against Western hegemony. What the West could offer Finally accepting that Crimea belongs to Russia, giving up all pretence of persuading or forcing Russia to return Crimea to Ukraine. With regard to the Donbas, Luhansk People’s Republic and Donetsk People’s republic the West should of course allow the people of these two regions to choose where they want to belong after a referendum. What is the point of continuing the eight-year long smouldering conflict at the border under the guise of a Minsk ceasefire agreement? All the lofty talk about no border revisions in Europe, seem to forget European history. Ending existing Russian sanction and threats of new foolish sanctions harming the West as much as they may harm Russia as sanction may not really harm those in power but everyone else. Opening up Russia to Western investment and collaboration on science and technology. Of course, subject to the condition specified above. Stop contributing to an escalation by sending more troops to countries at the border with Russia. It would be more important to finally have Western Europe contribute more to create its own credible defence, and not only relying whims of US presidents. Accepting for the moment Finlandisation of Ukraine, meaning acceptance of Russia’s demand that Ukraine would not join NATO. Accepting negotiations on those parts of the Russian demands that actually would benefit both Russia and the West. For instance, the “questions of ground-launched missiles bases” and a “New Start treaty on nuclear intercontinental-range delivery vehicles.” To avoid what would be appeasement on the Western side, all these concessions must only be made in return for equivalent concessions from Russia, which must be seen to be fulfilled within a set period. What the West might demand: Border guaranties from Russia Permanent withdrawal of combat troops to given distance from Russia borders with Eastern European Countries, demilitarisation of border areas. Transparency with inspections of mutual agreement, say on ground-launched missiles and troop withdrawal. New agreements on nuclear force reductions, with Russia and the U.S. with joint pressure on China to participate. Collaboration agreements to solve conflicts in other areas if the world, first and foremost of course North Korea, The Middle East, and Africa. Closer military collaboration. Perhaps with new organisation to substitute NATO and include Russia in order to create a mutual defence against existing and future threats in other parts of the World. While these ideas may sound naïve and farfetched in today’s climate of growing confrontation, they at least make an attempt to provide answers to the pertinent questions Henry Kissinger asked in relation to the West and Russia in 2017, in essence following up on Margaret Thatcher’s Fulton questions. Kissinger: “How should the West develop relations with Russia, a country that is a vital element of European security but which, for reasons of history and geography, has a fundamentally different view of what constitutes a mutually satisfactory arrangement in areas adjacent to Russia. Is the wisest course to pressure Russia, and if necessary to punish it, until it accepts Western views of its internal and global order? Or is scope left for a political process that overcomes, or at least mitigates, the mutual alienation in pursuit of an agreed concept of world order? Is the Russian border to be treated as a permanent zone of confrontation, or can it be shaped into a zone of potential cooperation, and what are the criteria for such a process? These are the questions of European order that need systematic consideration. “ https://www.henryakissinger.com/speeches/remarks-to-the-margaret-thatcher-conference-on-security/ Like Kissinger we must also realise that a realisation of our suggestions and ideas for some time “requires a defense capability which removes temptation for Russian military pressure.” Der Staat als maßgebende politische Einheit hat eine ungeheure Befugnis bei sich konzentriert: die Möglichkeit, Krieg zu führen und damit offen über das Leben von Menschen zu verfügen.“ (Carl Schmitt) European Peace is threatened “We face the risk of a major military conflict on our continent. Russia has amassed more than 100.000 troops and heavy equipment at the Ukrainian border. It is making open threats to use force unless its demands are met. At stake are the fate of Ukraine but also the wider principles of European security.” Josep Borell, High Representative of the EU. To see why peace is threatened and why Russia may threaten European security and peace we take a look at these topics: Russian demands and threats Western replies to Russian demands and Russian threats How Russians’ view a threat of war and sanctions The double-edged sword of sanctions Putin may have a point The foolish threat of sanctions A wiser reaction? Russian demands The Russian demands related to what is seen as essential to the security of The Russian Federation may be found in two Russian draft proposals for future agreements published on December 17, 2021. NATO agreement draft The first concern measures to ensure the security of The Russian Federation by keeping NATO at bay. The most important Russian demands are found in articles 4 to 7. Article 4 The Russian Federation and all the Parties that were member States of the North Atlantic Atlantic Treaty Organization as of 27 May 1997, respectively, shall not deploy military forces and weaponry on the territory of any of the other States in Europe in addition to the forces stationed on that territory as of 27 May 1997. With the consent of all the Parties such deployments can take place in exceptional cases to eliminate a threat to security of one or more Parties.). Article 5 The Parties shall not deploy land-based intermediate- and short-range missiles in areas allowing them to reach the territory of the other Parties. Article 6 All member States of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization commit themselves to refrain from any further enlargement of NATO, including the accession of Ukraine as well as other States. Article 7 The Parties that are member States of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization shall not conduct any military activity on the territory of Ukraine as well as other States in the Eastern Europe, in the South Caucasus and in Central Asia. The essential Russian demands are quite clear: Withdraw NATO forces to where they were in 1997, and refrain from any further enlargement of NATO. Ukraine would therefore not be able to join NATO, and neither would Finland and Sweden. Other demands may seem to constrain Russia just as much as NATO. US-Russia treaty draft The second set of demands is found in the shape of a proposal for a treaty between the U.S. and The Russian Federation. In the treaty proposal the main Russian demand is that neither the U.S. nor Russia shall use the territories of other States to prepare or carry out an armed attack against the other Party. In other word Russia demands that the U.S. shall refrain from establishing a military presence in states formerly members of the USSR. Here the important articles of the treaty proposal. Article 4 The United States of America shall undertake to prevent further eastward expansion of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and deny accession to the Alliance to the States of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. The United States of America shall not establish military bases in the territory of the States of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics that are not members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, use their infrastructure for any military activities or develop bilateral military cooperation with them. Article 5 The Parties shall refrain from deploying their armed forces and armaments, including in the framework of international organizations, military alliances or coalitions, in the areas where such deployment could be perceived by the other Party as a threat to its national security, with the exception of such deployment within the national territories of the Parties … Article 6 The Parties shall undertake not to deploy ground-launched intermediate-range and shorter-range missiles outside their national territories, as well as in the areas of their national territories, from which such weapons can attack targets in the national territory of the other Party. Article 7 The Parties shall refrain from deploying nuclear weapons outside their national territories and return such weapons already deployed outside their national territories at the time of the entry into force of the Treaty to their national territories. The Parties shall eliminate all existing infrastructure for deployment of nuclear weapons outside their national territories. Russian threats While the demands in Russia’s two draft proposals could be seen to represent a clear starting point for a serious dialogue with NATO and the U.S. Russia has found it necessary to accompany the proposals with a military posture that can only be seen as a threat of military intervention into the Ukraine. For some time now there has been a build-up of Russian troops all along Russia’s border with Ukraine. Now apparently followed by movement of Russian troops into Belarus. There are even some Russian forces in Transnistria (the breakaway state from Moldova), and Russian units in the Mediterranean are entering the Black Sea. In effect Russian Troops encircle and threaten all of Ukraine’s northern, eastern and southern borders. Various media put the number of Russian troops at around 100,000, armed with tanks, armoured, vehicles, artillery and missiles. Numbers that may be increasing at the moment with troops moving into in Belarus, although ostensibly just for joint manoeuvres. Thus, Russian troops would, when the ground and rivers are frozen, be able to enter Ukraine either from the north to Kyiv, from the south east into or through Luhansk and Donetsk, the self-proclaimed people’s republics, from the south via Crimea or any combination of these approaches. Keeping everyone guessing what Russia might do. In effect forcing Ukraine defence to spread its defence thin. https://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2022/01/26/ucrania-rusia-claves-tension-frontera-trax/ The military threats against Ukraine have awakened a rather lethargic West to almost frenetic rabbit-like activity. Mostly in the form hectic diplomatic activity and the continuous announcement of various unspecified counter threats. Rejection of Russian demands and offer of dialogue On January 26 the U.S. and NATO delivered their written response to the Russian demands, without at the time publishing the content of their response. From a speech by Secretary of State, Blinken, on the same day we get the first indication of the U.S. response. The Russian demand for guarantees that Ukraine would be kept out of NATO is rejected. Blinken: We make clear that there are core principles that we are committed to uphold and defend – including Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity and the right of states to choose their own security arrangements and alliances.” Later the written answers to the Russian demands were leaked to the Spanish newspaper El Pais. With respect to Russia’s demand that NATO refrains from further enlargement, the U.S. states: “The United Sates continues to firmly support NATO’s Open Door Policy” With regard to some of the other Russian demands for Russian security Blinken indicated that it might be possible to find areas where agreements could be reached. Blinken: “We’ve addressed the possibility of reciprocal transparency measures regarding force posture in Ukraine, as well as measures to increase confidence regarding military exercises and maneuvers in Europe. And we address other areas where we see potential for progress, including arms control related to missiles in Europe, our interest in a follow-on agreement to the New START treaty that covers all nuclear weapons, and ways to increase transparency and stability.” In essence the U.S. has flatly rejected Russia’s most important demands, while offering to have a dialogue about other subjects related to a mutual interest in security and transparency. Blinken; “we’re prepared to move forward where there is the possibility of communication and cooperation if Russia de-escalates its aggression toward Ukraine, stops the inflammatory rhetoric, and approaches discussions about the future of security in Europe in a spirit of reciprocity.” The leak to El Pais reveals that the U.S. is “prepared for a discussion of the indivisibility of security – and out respective interpretations of that concept – as raised in Article 1 of Russia’s draft bilateral treaty.” Furthermore “The United States is willing to discuss conditions-based reciprocal transparency measures and reciprocal commitments by both the United States and Russia to refrain from deploying offensive ground-launched missile systems and permanent forces with a combat mission in the territory of Ukraine.” The U.S. is prepared to discuss the question of ground-launched missiles bases in Romania and Poland provided Russia is prepared to discuss the same for Russian bases of the U.S. choosing. The U.S. is also willing to discuss follow up to the New Start Treaty on nuclear intercontinental-range “delivery vehicles.” Blinken said that NATO would deliver their own response, indicating that the U.S. and NATO responses would be reinforce each other, with “no daylight “between the U.S. and its allies. This is confirmed by the leak to El Pais in which NATO “reaffirm our commitment to NATO’s Open Door policy under Article 10 of the Washington Treaty.” Thus, rejecting Russia’s main demand. NATO also expresses regret that “Russia has broken the trust at the core of our cooperation and challenged the fundamental principles of the global and Euro-Atlantic security architecture.” A written Russian reply is awaited, but Lavrov and Putin have already indicated their dissatisfaction with the answer received from the U.S. and NATO. Lavrov: "As for the key issue that generally prompted us to turn to the United States and the North Atlantic alliance with the initiative, the reaction was negative … "the Americans prefer to focus on discussing still important but secondary issues” (Tass). At a meeting with Hungary’s Prime Minister Orban, Putin also vented his dissatisfaction. According to Tass “He explained that Moscow had seen no adequate response to three key demands - preventing NATO’s expansion, non-deployment of strike weapons systems near Russian borders and returning the military infrastructure of NATO in Europe to the positions existing in 1997 when the Russia-NATO Founding Act was signed.” Countering the Russian threats The threatening Russian military posture against Ukraine has been met with a chorus of condemnation in the West, accompanied by various diffuse and nebulous counter threats if Russia should invade Ukraine. No troops, but material for Ukraine While the West has made it abundantly clear that Western troops would not enter Ukraine in case of a Russian invasion, Western countries have contributed materially to Ukraine’s ability to defend itself against an invasion. This has included much publicised deliveries of anti-tank missiles from the U.S. (Javelin missiles) and the UK (NLAW’s or Next generation Light Anti-tank Weapons). Not all allies have been willing to contribute though. Germany will not deliver weapons to Ukraine, variously arguing that they do not deliver weapons in areas of conflict (although this is the only place they are needed) or mentioned reasons related to their own history. A request for helmets from Ukraine, has been met with the laughable offer of delivering 5.000 helmets. Germany has not even answered a request from Estonia to allow the export of guns to Ukraine. Guns that Estonia hat got from old GDR (The German Democratic Republic) stocks. The U.S. is sending extra troops to frontline NATO countries, with up to 2,000 troops from the elite 82nd airborne division being send to Poland from the U.S. and almost 1.000 troops to Romania from German bases. The Germans have promised to send 375 additional troops to Lithuania, while UK is talking about sending 350 Royal Navy marines to bolster Poland’s defence. How that helps the Ukraine is difficult to see, instead it might actually reinforce Russia’s claim that NATO is threatening Russia, and thus bring about reciprocal moves by Russia. Making the whole situation even more unstable. Very diffuse threats of crippling sanctions At a press conference in January President Biden was asked if the West hadn’t lost all its leverage over Vladimir Putin, as it wouldn’t “put troops on the line” and sanctions hadn’t worked in the past. Biden gave a somewhat rambling answer arguing “Well, because he’s never seen sanctions like the ones I promised will be imposed if he moves, number one … I think what you’re going to see is that Russia will be held accountable if it invades.” Then adding “And it depends on what it does. It’s one thing if it’s a minor incursion and then we end up having a fight about what to do and not do, et cetera.” As we argued in a previous blog entry Biden’s answer actually indicates that if Russia made a limited invasion the Western allies might squabble and disagree among themselves, and therefore not be able to agree on crippling sanctions. Just a few hours later Press Secretary Jen Psaki corrected Biden, stating “If any Russian military forces move across the Ukrainian border, that's a renewed invasion, and it will be met with a swift, severe, and united response from the United States and our Allies”. This was followed by similar corrections from Blinken and even President Biden himself. But the damage had been done. Might Putin actually get away with a small incursion? On sanctions there also seems to be a lot of confusion. The only thing the allies seem to agree upon publicly is that if Russia invades it will be met with very severe sanctions. What sanctions and how severe is still not clear. Robert Menendez, Chairman of the Foreign relations Committee, bombastically announced the U.S. is preparing “the mother of all sanctions.” Arguing that the package of sanctions being prepared would make the financial cost of Russian aggression extremely high. It would involve “massive sanctions against the most significant Russian banks, crippling to their economy, meaningful in terms of consequences to the average Russian in their accounts and pensions.” (voanews.com) There has been talk denying Russian banks access to SWIFT (The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial telecommunication) which is used to communicate money transfers between banks. But Russian bank transfers apparently only make up 1.5 % of the up to 42 million daily transfer messages, and denying access to SWIFT might lead Russia and China to look for alternatives. The U.S. has aired the possibility of cutting Russia off from the supply of critical goods such as computer chips. Not only supplies from the U.S., but from all supplies using U.S. made chips. Liz Truss, The UK Foreign Secretary, has warned that Russian oligarchs’ who are supporting Putin, will be met with sanctions in the UK, and oligarch’s have significant investments in London’s property market, meaning that it may not be an entirely empty gesture. Then there is German problem. What about Nordstream 2? Would Germany be willing to use Nordstream 2 as part of program to sanction Russia in case of Russian invasion? Listening to Chancellor Scholz it seems doubtful, as he argued in December 2021 that the gas pipeline was a private project to be kept out Ukraine crisis. Later he and his Green party Foreign Minister have said that all is on the table when talking about sanctions, thus perhaps indicating a change of mind. But Germany has certainly not been eager to open up about what it might contribute to “a mother of all sanctions” package. No doubts because Germany is in a precarious position given that it is relying heavily on the import of Russian gas and has a substantial trade with Russia Would sanctions even work? At the beginning of February, it is still difficult to see what sanctions the U.S. and its allies can agree upon. And does a threat of diffuse and not yet agreed upon sanctions really hold Russia back. It is very difficult to know if threats of “mother of all sanctions” will scare Putin and “Mother Russia” and prevent Russian invasion of Ukraine or even a withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine’s border. The double-edged sword of sanctions While the U.S. may be preparing “the mother of all sanctions” without too high a cost to themselves, the European allies have a problem when planning for serious sanctions on Russia. The EU is dependent on Russian gas import for a foreseeable future. One just need to take a look at the market shares of most important suppliers of natural gas to Europe to see the problem. While sanctions closing off the supply from Russia would certainly hurt the Russian economy, it might hurt Europe even more. And whatever sanctions the EU may decide upon, Russia could always use the threat of stopping the Russian energy supply to hurt Europe. Here a diagram of main suppliers of natural gas to Europe. (The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies): https://www.oxfordenergy.org/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Russian-gas-amid-market-tightness.pdf The import of gas from Russia through already existing pipelines make up between 30% and 35%, of the EU’s supply, while the second most important supplier Norway delivers less than 25% of the EU’s natural gas supply. Natural gas is used for winter heating, electricity generation and industrial production. According to S&P Global Platts Russia is set to remain the dominant gas supplier to Europe up to 2040, according to the latest long-term European gas outlook. The outlook even predicts that the import from Russia and thus the dependence on Russia, may rise to 40% in the years ahead. While import from Norway may decline in the same period to almost half of the present volume, as the supply from Norwegian gas fields are diminishing. This winter Russia has already given Europe a foretaste of the problem facing Europe due to dependence on Russian gas. At the time when demands spiked in Europe Russia reduced the supply of gas, ostensibly due to technical problems, although Putin has said that the Europeans could just asked for more gas. The reduced supply from Russia and low winter storage level for gas in the West let prices spike. According to The Council of Foreign Relations the EU is also dependent on Russia for more than a quarter of its imports of oil. All in all, Russia is the EU’s largest single source of energy. Germany is always wary of discussing sanctions on Russia as it is especially dependent on Russian gas supplies. Data from Statista show that in 2020 Russia supplied 55.2% of the German demand for natural gas. Norway stood for 30.6% and the Netherlands for 12.7%. Underlining the German dependence on Russia is the Russian share of its import of oil. According to data from Statista Russia supplies around 33% of Germany’s import of oil. Furthermore, the coal import from Russia makes up around 45% of the total supply. We may conclude that Europe and Germany especially are in a bind. How can they introduce crippling sanctions on Russia in case of an invasion of the Ukraine? Which by the way houses one of gas transit pipelines to the rest of Europe (making evident why Germany sees a need for Nordstream 2). And it gets worse. Europe has important trade relations with Russia. The EU is Russia’s largest trading partner, 36.5% of Russia’s imports came from the EU and 37.9% of its exports went to the EU. Russia is the EU’s fifth largest trading partner representing 4.8% of the EU’s trade. The EU first and foremost exporting machinery and transport equipment, followed by chemicals and manufactured goods. Whole Russia’s export to the EU is dominated by energy export and raw materials. Again, a degree of interdependence that would make it hard for the EU to initiate crippling sanctions on Russia without fearing costly retaliation from Russia. Getting out of the gas bind? How may Europe become less dependent on Russian energy supplies in the short run? If we are to believe Secretary of State Blinken, the U.S. and Europe has done “a tremendous amount of work to mitigate any effects of sanctions on those...imposing them, as well as any retaliatory action that Russia might take.” Words words,... Blinken always seems to engaged in a kind of nervous staccato word feud, but what about actions? The Biden administration has announced that is “working with gas and crude oil suppliers from the Middle East, North Africa and Asia to bolster supplies to Europe in the coming weeks, in an effort to blunt the threat that Russia could cut off fuel shipments in the escalating conflict over Ukraine.” (NYT) The effort involves attempts to step up deliveries of LNG (liquefied natural gas) from the especially from U.S., but also from Qatar and elsewhere. No wonder Biden is awarding Qatar a special status as “None NATO ally.” As Qatar has 12.5% of the World’s proven gas reserves, while the U.S. only has 5.3%. Russia by the way has 24.3%. But would it actually be possible to substitute even a small part of the Russian gas supplies to Europe with LNG transported in a fleet of LNG ships? It will be difficult to raise production to cope with extra demand. There is also a serious problem of not enough LNG terminals in Europe. Germany apparently has none. Then there is problem with distribution. Meaning that European gas supplies will take a major hit if Russian deliveries were cut off. While it could be argued that this would certainly hurt Russia’s economy. Russia seems be busy trying to alleviate this problem, by planning for larger gas deliveries to China, having initiated the building of a new pipeline from major gas fields to China. “Known as Power of Siberia 2, the mega-pipeline traversing Mongolia will be able to deliver 50 billion cubic meters of Russian gas to China annually. It was given the go- ahead in March by Russian President Vladimir Putin, and when finished it will complement another massive pipeline, Power of Siberia 1, that transports gas from Russia’s Chayandinskoye field to northern China” (voanews.com) Putin may have a point What seems to irk Putin is NATO’s Eastern expansion and here of course the possibility that Ukraine would join NATO. We have already seen that Russia’s main demand is an ironclad assurance that Ukraine will not be able to join NATO. In the West we may wonder why this demand so important, as NATO certainly does not threaten Russia in any way. Looking back to the time the USSR disintegrated and the DDR was reunited with Western Germany, we may actually find that Putin has a point, when criticizing NATO expansion. Here an excerpt from a written note indicating that Secretary of State James Baker gave the Russian Foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze a promise during a conference in 1990. "And if U[nited] G[ermany] stays in NATO, we should take care about non-expansion of its jurisdiction to the east." “Not an inch eastward” James Baker is reported to have assured Mikhail Gorbachev in relation to NATO, during the complicated negotiations relating to the German re-unification. Baker assured Gorbachev “neither the president nor I intend to extract any unilateral advantages from the processes that are taking place,” and the Americans understood the importance for the USSR and Europe of guarantees that “not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction.” Gorbachev Foundation Archive, Fond 1, Opis 1. (nsarchive.gwu.edu) Later the West has argued that Baker’s promises were just part of the initial discussions. The final treaty on the German re-unification, the so-called Two plus Four Treaty does not contain such guaranties. It only mentions that German NATO troops, but no foreign armed forces, would be allowed to be stationed on former East German territory. Nothing about further NATO expansion towards the east. Here one has to remember that no one could foresee what happened after 1990, when former members of the USSR broke free and became members of NATO. Russia may also refer to an agreement found in “The Istanbul Document” from an OSCE Summit in 1999. It states that “Each participating State has an equal right to security. We reaffirm the inherent right of each and every participating State to be free to choose or change its security arrangements, including treaties of alliance, as they evolve. Each State also has the right to neutrality. Each participating State will respect the rights of all others in these regards. They will not strengthen their security at the expense of the security of other States.” Somewhat contradictory, the agreement states that “every participating State to be free to choose or change its security arrangements, including treaties of alliance.” But it also states that “They will not strengthen their security at the expense of the security of other States” In a letter to the West Lavrov refers to this document and argues that the West is breaking the agreement by strengthening their security at the expense of the security of Russia. In a rambling answer to a question at a press conference even Biden seems to express understanding for Putin’s and Russia’s predicament: “I think that he is dealing with what I believe he thinks is the most tragic thing that's happened to Mother Russia in that the Berlin Wall came down, the empire has been lost, the near abroad is gone.” Of course, Putin may only be using the postulate of broken promises by the West to hide his real reasons for wanting to prevent NATO expansion towards the east. Putin has said that he sees the collapse of the Soviet Union as “a major geopolitical disaster of the century. As for the Russian nation, it became a genuine drama. Tens of millions of our co-citizens and co-patriots found themselves outside Russian territory. Moreover, the epidemic of disintegration infected Russia itself.” Russia may have a point in relations to the West’s self-proclaimed values and rule based political stance. In Foreign Minister Lavrov’s view: “Serious, self-respecting countries will never tolerate attempts to talk to them through ultimatums and will discuss any issues only on an equal footing. As for Russia, it is high time that everyone understands that we have drawn a definitive line under any attempts to play a one-way game with us. All the mantras we hear from the Western capitals on their readiness to put their relations with Moscow back on track, as long as it repents and changes its tack, are meaningless. Still, many persist, as if by inertia, in presenting us with unilateral demands, which does little, if any, credit to how realistic they are.” (Sergey Lavrov, June 2021). What bothers Russian leaders may be the view that the West thinks it is can issue dictates to Russia, seeing it as a state in decline. Illustrated by President Obama’s rather derogatory remark when Russia invaded the Crimea: “Russia a “regional power” that had seized part of Ukraine out of weakness rather than strength.” Today a self-assured and perhaps somewhat arrogant U.S. and its allies joined in NATO, argues that former members of Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, now independent states, have every right to join NATO, and that this will contribute to security and stability. “When NATO invites other European countries to become Allies, as foreseen in Article 10 of the Washington Treaty and reaffirmed at the January 1994 Brussels Summit, this will be a further step towards the Alliance's basic goal of enhancing security and stability throughout the Euro-Atlantic area, within the context of a broad European security architecture.” Well, in the present situation insisting on the right of Ukraine to join NATO certainly does not contribute to stability and overall security. In fact, NATO itself mention “States which have ethnic disputes or external territorial disputes, including irredentist claims, or internal jurisdictional disputes must settle those disputes by peaceful means in accordance with OSCE principles.” One would think that that in itself would preclude that Ukraine could join NATO, as it certainly has outstanding territorial disputes. Perhaps the West and NATO should therefore be somewhat more accommodating in relation to Putin’s demands, and focus instead on initiatives that would enhance better relations with Russia in the long run. How Russians´ view a threat of war and sanctions How does the Russian population view the present crisis compared to compared to other problems and previous crises? The Russian Levada Center recently presented a diagram showing how the Russian population see the present crises potential compared to earlier views: NB: The Levada Center is apparently included in the registry of non-commercial organizations acting as foreign agents.

Only about 25% of respondents see a present potential for armed conflict with USA and NATO, but this percentage is on a growing path, and significantly it is now even higher than in the years before the Crimea invasion. The potential for an armed conflict with a neighbouring country is seen by around 35%, but also here percentages are on a rapidly rising path. Even so the Russian population seem more preoccupied with potential mass epidemics, an economic crisis and protests and industrial disasters. An earlier study by the Carnegie Moscov Center, using focus groups, indicate that “The Kremlin has been able to foster a mythological sense of heroism when it comes to war. It has helped war to acquire an aura of justice. After all, a besieged fortress needs to be protected. That helps convince the public that external aggression is actually part and parcel of a defensive war—or just part of a series of simple, low-cost military operations.” Significantly it was also found that 61% of elderly Russians, aged 55 or above, believed that USA and NATO were responsible for the conflict escalation in Ukraine. While only around 24% of those aged 18 to 24 supported this opinion. What about sanctions then? In January 2022 the Levada Center found that “The perception of sanctions has not changed significantly compared to February 2020: 35% of respondents are not worried about sanctions at all. The proportion of Russians who believe that Western sanctions affect only a narrow circle of people responsible for Russian policy towards Ukraine has doubled to 41%.” So, the Russians in general do not seem scared by the threat of sanctions, meaning perhaps that sanctions represent a rather blunt instrument. Thus, sanctions do not seem to really deter Russia The foolish threat of sanctions The discussions of the Western threat of using sanctions to somehow force Russia and Putin to stand down indicate that the threat of sanctions may be foolish. Sanctions until now are so diffuse that that in itself may not really scare Russia and prevent some kind of incursion into Ukraine or attempts to install a more Russian friendly government. To be believable sanctions ought to be concrete and stated in advance, not hidden in a nebulous cloud of word streams and expressions like “the mother of all sanctions”. It Russia does not believe in the diffuse threat of sanction and wordy declarations of unity among the allies, it might certainly dare in some engage form of aggression, either outright invasion or something else. What then? There is a nagging doubt with respect to the postulated unity of the Western allies with regard to sanctions. Perhaps clearly indicated by the difference in President Biden’s and Chancellor Scholz’s reactions to a question about whether Nordstream 2 would be included in sanctions. Biden saying: “If Germany — if Russia invades — that means tanks or troops crossing the — the border of Ukraine again — then there will be — we — there will be no longer a Nord Stream 2. We will bring an end to it.” While Scholz gave a non-answer: I want to be absolutely clear: We have intensively prepared everything to be ready with the necessary sanctions if there is a military aggression against Ukraine … We will act together jointly.” Sanctions after an invasion would of course hurt Russia, but would hardly cripple Russia and make them withdraw. Let us say Ukraine is invaded, perhaps with Russian troops entering Luhansk and Donetsk and further parts of south eastern Ukraine. If the West then finally agreed to engage in “the mother of all sanctions, what would be achieved? Would it make Russia pull back? Hardly, once they had entered Ukraine. In that case sanctions would no longer help Ukraine, nor anyone else. In essence one might say the most efficient use of sanction is when they create a believable threat in advance of any invasion, but how is that possible with the present very diffuse threat of sanctions. We have seen sanctions that would hurt Russia would also hurt the West, especially of course those dependent on the import of Russian energy supplies and reciprocal trade. Meaning that the West may shoot itself in the foot to hurt Russia. Not very smart, especially if sanctions were to run for some time. It would certainly result in energy supply problems in the West, and price rises. If Russia made a major incursion we would expect a high number dead on both sides, but also a large number of refugees streaming from a Ukraine at war to the West. How would the West cope with say a million or even several millions of Ukrainian refugees? Russian invasion and Western counter actions would certainly open a new, very cold war, accompanied by threatening military postures on both sides. There is a risk that the dispute between Russia, on the one hand, and the United States and the European Union on the other, will lead to a foolish mutual loss-loss situation with diminished opportunities for both sides. At the same time as there is a rapidly growing Chinese elephant in the room and dangerous developments in both the Middle East/Iran and Africa posing a serious threat to a weak Europe. Crippling sanctions, a cold war between East and West, and a military build-up along the borders would be certain to drive Russia into the arms of China. Do we want that? To be confronted with two military super powers in many areas, resources, trade, influence in the rest of the world and in space? No, we certainly would not, then what? A wiser reaction? While on an official visit to India in January 2022 the chief of the German navy created furore when he was caught on video talking about relations with Russia. “The Crimean Peninsula is gone, it will not come back, that is a fact… what Putin really wants is respect on an equal footing. And - my God - showing respect to someone costs next to nothing, costs nothing. So you would ask me - but you don't ask me -: It's easy to give him the respect he demands - and which he probably deserves." (Vice-admiral Kay-Achim Schönbach). He also waded into the present conflict arguing that Ukraine did not meet the conditions for membership of NATO, because part of the country was occupied by another country. “By the Russian army, or, as Russia claims, by militias". Making the faux pas complete he argued China represented a greater threat than Russia, and that we therefore “need Russia against China” The Admiral certainly put his foot in it, and when his views became public, he had to resign from the German navy. But perhaps what the German admiral said really cut to the chase, presenting a much more realistic view of what the West must realise, and indicating a wiser path to tone down the conflict with Russa and Putin. Before the German Admiral punctured the baloney of the present Western views, more illustrious persons had asked questions that would seem to pay similar respect to Russia. First and foremost, Margaret Thatcher. In 1996 in Fulton Missouri, fifty years after Churchill’s famous speech on the iron curtain in Europe, Thatcher asked four questions facing NATO with regard to Russia: “Should Russia be regarded as a potential threat or a partner? (Russia may be about to answer that in clearer fashion than we would like.) Should NATO turn its attention to "out of area" where most of the PostCold War threats, such as nuclear proliferation, now lie? Should NATO admit the new democracies of Central Europe as full members with full responsibilities as quickly as prudently possible? Should Europe develop its own "defence identity" in NATO, even though this is a concept driven entirely by politics and has damaging military implications?” Today these questions seem more pertinent than ever and like the Admiral they cut right through to the essence. Now, do we think that the response from West to the present conflict represent adequate answers to these questions? Or do they rather indicate narrowminded and confused views, an unholy mishmash of Western values, unfounded trust in Western unity, disregard for the Russian views, rejection of power politics and realism, disregard for the risk that the U.S. may be a World Power in decline and the EU a military dwarf. In other words, totally unrealistic and ignoring how much the West will have a need for at least quiet cooperation with Russia in face of the Chinese striving for World hegemony. Trump may have been the first U.S. President to realise that the U.S. has a need for good relations with Russia. That President Trump’s views on foreign policy and here, especially in relation to Russia, may have been prescient is acknowledged in a special report published by The Council on Foreign Relations in 2019. “Whereas the president’s default attitude toward virtually every other major country in the world is highly critical and he insists that the United States has been getting a “bad deal,” he has consistently shown sympathy and understanding for Russian perspectives and suggested it would be “nice if we actually could get along.” In November 2017, Trump said he hoped to find a way to lift sanctions on Russia to promote cooperation.” (cfr.org) On Twitter Trump wrote “When will all the haters and fools out there realize that having a good relationship with Russia is a good thing, not a bad thing,” and added, “I want to solve North Korea, Syria, Ukraine, terrorism, and Russia can greatly help!” Instead of sanction on Russia Trump argued “our country must move on to bigger and better things.” During his first year as president, he even suggested that the U.S. and Russia should create a joint cybersecurity unit. Perhaps a somewhat naïve idea at the time, it showed that he viewed Russia more as a potential partner than an adversary. Trumps views were apparently shared in Russia demonstrating that Russia had high hopes for better relations with the US when Trump became President. An article published in 2019 from Carnegie Moscow Center describe the Russian hopes: “Despite his colorful personality, in the words of President Putin, Trump appealed to Russian expectations of an American president who would put ideology to one side and adopt a realistic view on international relations and conduct a foreign policy squarely based on national interests. Such an American leader, it was hoped, would be amenable to a series of trade-offs with Russia, a sort of a “grand bargain.” Once the deal was done, the hope in the Kremlin was, the unfortunate page in the US-Russian relations created by the Ukraine crisis, would be turned. The Ukraine issue would be settled on terms that would be acceptable to Russia; the US sanctions imposed in the wake of events in Crimea and Donbass would be lifted; and Moscow and Washington would resume collaboration on an equal basis in places such as Syria, Afghanistan, and North Korea.” These hopes were squashed on both sides of the Atlantic when accusations of Russian interference in the presidential election popped up (See the Muller Report) and Trump was accused of collusion with Russia. His meetings with President Putin were regarded with distrust in the West. As result Trump was forced to put the relation between the U.S. and Russia into a deep freezer. When Congress in 2017 voted for the sanctions bill “Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act” Trump gave this critical comment: ”By limiting the Executive’s flexibility, this bill makes it harder for the United States to strike good deals for the American people, and will drive China, Russia, and North Korea much closer together." An important possibility for creating better relations and even partnerships in World affairs based upon cleareyed power politics with less focus on idealistic Western views of values crumbled and laid the ground for the present animosity and conflict between Russia and the West. No wonder that Russia turned to China. In the view of a Chinese professor on international relations: “China, Russia had ‘no choice’ but to strengthen strategic and military ties in the face of G7 and NATO.” (scmp.com) In February 2022 President Putin confirmed the growing orientation towards China in an article in Xinhua. Apart from his emphasis on the growth in trade and cooperation on energy supplies he wrote: “The coordination of the foreign policy of Russia and China is based on close and coinciding approaches to solving global and regional issues. Our countries play an important stabilizing role in today's challenging international environment, promoting the democratization of the system of interstate relations to make it more equitable and inclusive. We are working together to strengthen the central coordinating role of the United Nations in global affairs and to prevent the international legal system, with the UN Charter at its centre, from being eroded.” (en.kremlin.ru) A few days later Xi Jinping mirrored Putin’s view. He said the two countries are firmly supported each other in upholding their respective core interests, and have enhanced their political and strategic mutual trust, adding that bilateral trade between the two countries has hit a record high. “Xi noted the two sides have actively taken part in the reform and development of the global governance system, practiced true multilateralism, and safeguarded true democratic spirit. He added that these efforts have galvanized the solidarity of the international society to tide over this difficult time and upheld international equity and justice.” Of course, China also supported the Russian view in the present conflict with Ukraine and on Russian security. China might even help Russia overcome problems caused by Western sanctions. While the cooperation between China and Russia certainly is to China’s advantage, not the least in relation to its problems with the West, it may actually be less advantageous to Russia in the long run. Russia will over time become a very minor partner more dependent on China that it may wish for. Even more problematic China may represent further trouble for Russia, as China sooner or later may be eyeing the vast reserves of energy and other resources in the sparsely populated Siberia. Thus, Russia in the long run may be just as much need in of cooperation with the West as the West may have for cooperation with Russia to the counter the Chinese hegemon. That is why the present conflict with Russia is handled very foolishly by West, actually meaning that the West may harm itself much more than it may harm Russia. Not surprisingly there is an urgent need to revise Western policy and strategy along the lines preferred by Trump. Today’s Western leaders with their ballooning and airy word streams about values, democracy, will have great difficulty in accepting that. Perhaps with the exception of Macron (who may have his own reasons) and leaders in South East Europe like Viktor Orban. What then would be necessary in a realistic power exchange with Russia? Some ideas for what the West could offer and what it might demand in return. Ofcourse only if and when Russia within a set period could demonstrate adherence to what the West wants in turn. (See also the essay “Reacting to imagined russian threat, overlooking giant chinese elephant”) What the West could offer: Finally accepting that Crimea now belongs to Russia, giving up all pretence of persuading or forcing Russia to return Crimea to Ukraine. With regard to the Donbas, Luhansk People’s Republic and Donetsk People’s republic the West should of course allow the people of these two regions to choose where they want to belong after a referendum. What is the point of continuing the eight year long smouldering conflict at the border under the guise of a Minsk ceasefire agreement? All the lofty talk about no border revisions in Europe, seem to forget European history. Ending existing Russian sanction and threats of new foolish sanctions harming the West as much as they may harm Russia as sanction may not really harm those in power but everyone else. Opening up Russia to Western investment and collaboration on science and technology. Ofcourse subject to the condition specified above. Stop contributing to an escalation by sending more troops to countries at the border with Russia. It would be more important to finally have Western Europe contribute more to create its own credible defence, and not only relying whims of US presidents. Accepting for the moment Finlandisation of Ukraine, meaning acceptance of Russia’s demand that Ukraine would not join NATO. Accepting negotiations on those parts of the Russian demands that actually would benefit both Russia and the West. For instance, the “questions of ground-launched missiles bases” and a “New Start treaty on nuclear intercontinental-range delivery vehicles.” To avoid what would be appeasement on the Western side, all these concessions must only be made in return for equivalent concessions from Russia, which must be seen to be fulfilled within a set period. What the West might demand: Border guaranties from Russia Permanent withdrawal of combat troops to given distance from Russia borders with Eastern European Countries, demilitarisation of border areas. Transparency with inspections of mutual agreement, say on ground-launched missiles and troop withdrawal. New agreements on nuclear force reductions, with Russia and the U.S. with joint pressure on China to participate. Collaboration agreements to solve conflicts in other areas if the world, first and foremost of course North Korea, The Middle East, and Africa. Closer military collaboration. Perhaps with new organisation to substitute NATO and include Russia in order to create a mutual defence against existing and future threats in other parts of the World. While these ideas may sound naïve and farfetched in today’s climate of growing confrontation, they at least make an attempt to provide answers to the pertinent questions Henry Kissinger asked in relation to the West and Russia in 2017, in essence following up on Margaret Thatcher’s Fulton questions. Kissinger: “How should the West develop relations with Russia, a country that is a vital element of European security but which, for reasons of history and geography, has a fundamentally different view of what constitutes a mutually satisfactory arrangement in areas adjacent to Russia. Is the wisest course to pressure Russia, and if necessary to punish it, until it accepts Western views of its internal and global order? Or is scope left for a political process that overcomes, or at least mitigates, the mutual alienation in pursuit of an agreed concept of world order? Is the Russian border to be treated as a permanent zone of confrontation, or can it be shaped into a zone of potential cooperation, and what are the criteria for such a process? These are the questions of European order that need systematic consideration.“ (henryakissinger.com). Like Kissinger we must also realise that a realisation of our suggestions and ideas for some time “requires a defense capability which removes temptation for Russian military pressure.” |

Author

Verner C. Petersen Archives

May 2024

|