|

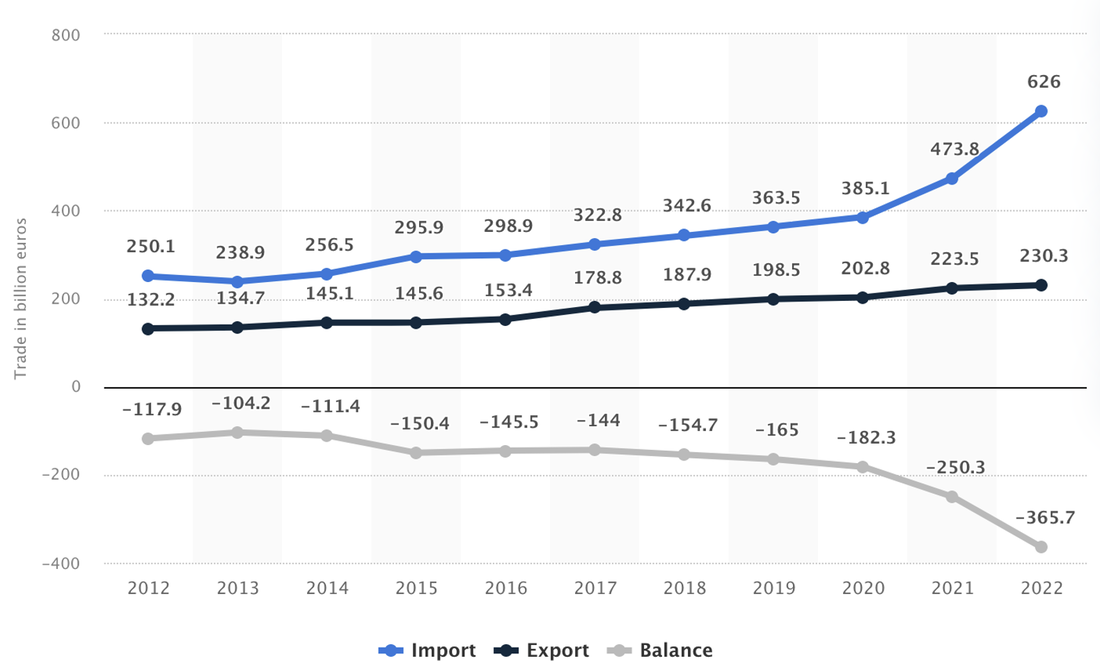

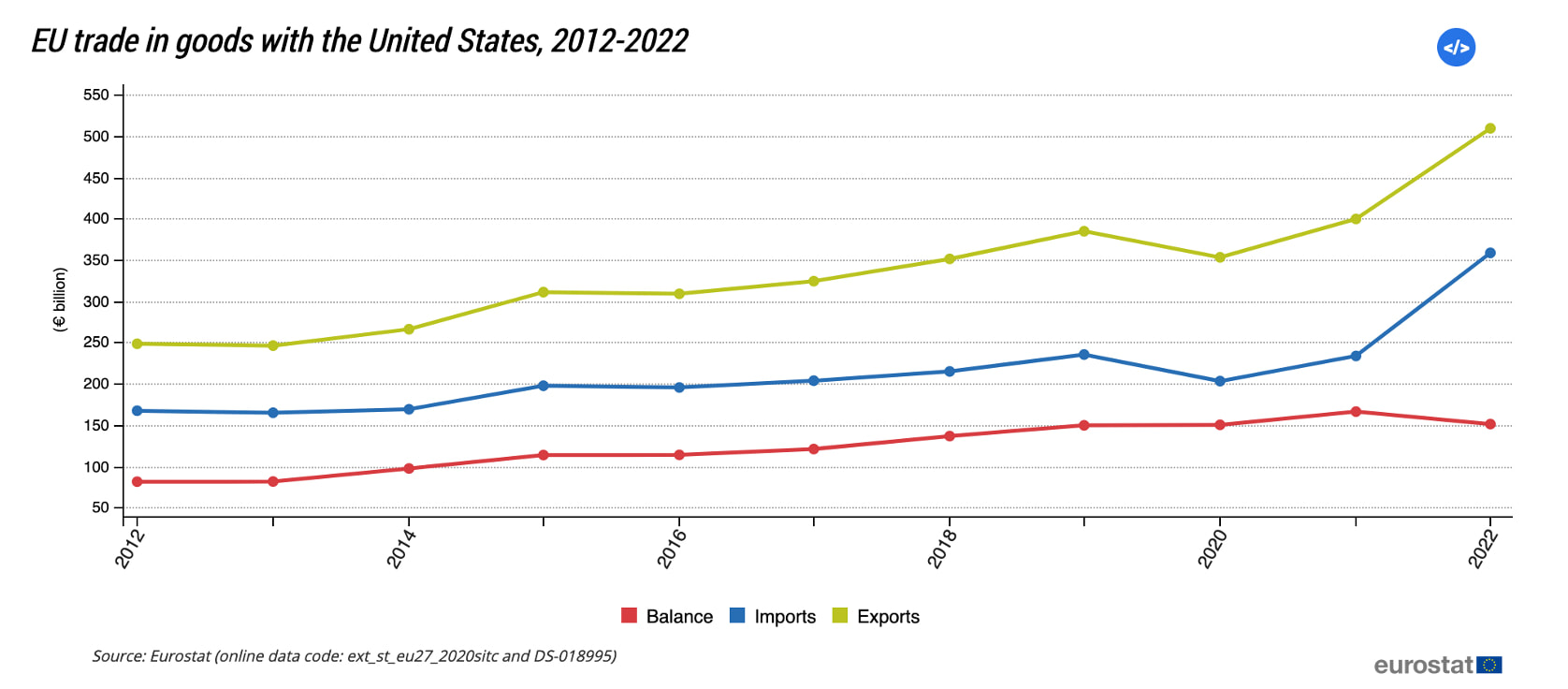

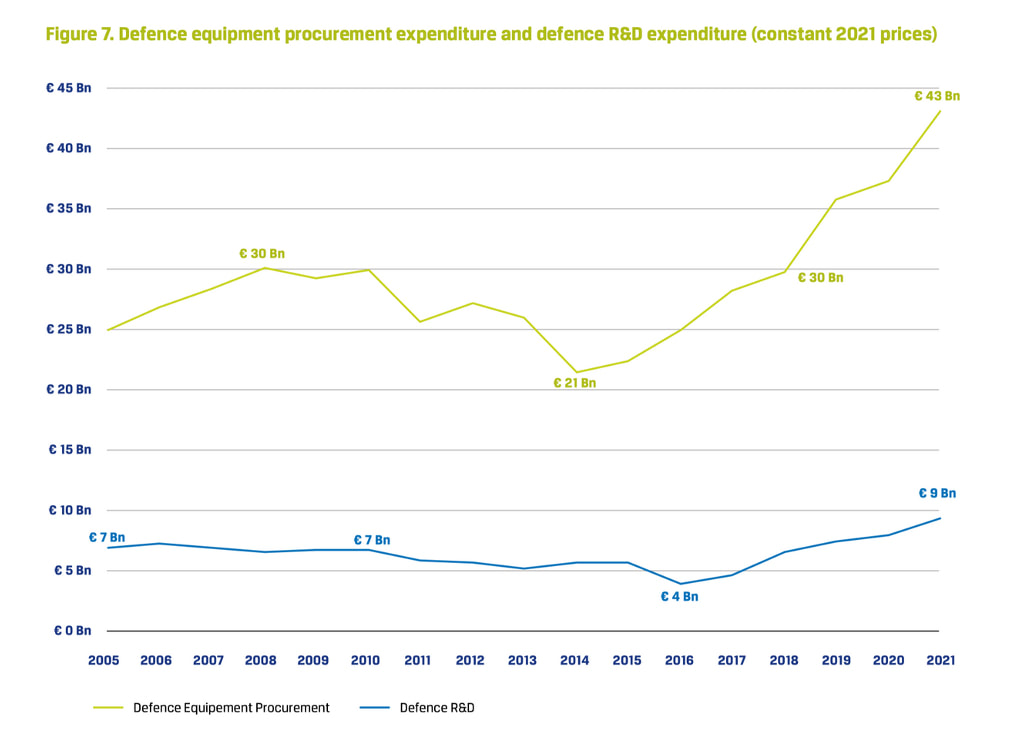

The circle of stars in EU flag is meant to symbolize unity Macron’s much maligned ideas on European strategic autonomy deserve a serious discussion, realising that Europe today is getting caught like pawn between a hegemonic U.S. and a China striving for hegemony. In order to discuss the question of European autonomy or perhaps the lack of it, this second part of an essay will to take a much closer look at the following topics: In part two: No European energy independence European trade dependencies No European defence autonomy “The elephant in the room” key problem for European autonomy No European energy independence Europe’s energy dependency measured as the extent to which it relies on imports to meet its energy needs came to 55.5 percent in 2021. Before the War in Ukraine “Russia’s natural gas accounted for roughly 45% of all EU gas imports in 2021. Combined with 25% of oil and 45% of coal imports, Europe paid around €400 billion to Russia last year for its energy supply. That’s a number comparable to the annual GDP of Germany.” (investigate-europe.eu). Numbers that really demonstrated EU’s dependence on Russia for its energy needs, absolutely no signs of European autonomy here. In the almost panicky attempts to get rid of the dependence on Russia the EU went far and wide to find alternative sources for its energy need. For instance, starting the import of LNG from the US and the Near East and like Germany hastily borrowing mobile LNG terminals. At the same time trying to reduce the energy consumption with all sorts of initiatives. Not really a durable way to reduce dependence on others for energy needs. In May 2022 the EU presented the so-called REPowerEU Plan. A plan for a more durable long-term solution to its energy needs. “The measures in the REPowerEU Plan can respond to this ambition, through energy savings, diversification of energy supplies, and accelerated roll-out of renewable energy to replace fossil fuels in homes, industry and power generation. (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_3131). European trade dependencies A look at the EU’s most important trading partners may also tell us something about the relative weight of the of the U.S. vs China: Trade in goods with China (Statista): The figure indicates that the EU is heavily dependent on relations with China for trade in goods, and trade with China has grown rapidly in the last few years, indicating a growing dependence on trade with China. While trade in services has much less weight. In December 2020 the EU and China in principle agreed on the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, the so-called CAI, opening up the markets and contributing to establishing a level playing field. The agreement has not been ratified as the EU has since become more critical in its China policies. Now how does trade with U.S. compare to trade with China? Trade in goods with the U.S. EU exports in goods to the U.S. reached 509.3 billion euros in 2022, while imports stood at 358.4 billion euros. EU exports to China in the same year reached 230.3 billion euro, while imports reached 626 billion euro. Comparing the EU’s trade relations with China and U.S. show that imports from China are far larger than imports from the U.S. For exports the relation is reversed, EU exports to the U.S. are far larger than to China. The total picture, of import and export, especially when one includes trade in services, where the U.S. is much more important than China, show that the U.S. is still the most important trading partner in 2022 by a small margin. The continuing rise in trade and the numbers would seem to indicate a kind of reciprocal interdependence in EU trade relations both with China and the U.S. But there are signs that relations may be souring in the future both in relation to China and to the U.S. In relation to China because a European attempt to have your cake and eat it too, meaning a de-risking policy with no de-coupling from China. “We know there are some areas where trade and investment poses risks to our economic and national security, particularly in the context of China’s explicit fusion of its military and commercial sectors,” von der Leyen said i her speech on China on March 30, 2023. The proposed CAI has more or less been laid to rest. The recently proposed EU Industrial Act is intended to make it slightly more difficult for Chinese firms to participate in EU public procurements. The EU Critical Materials Act the EU is an attempt to free the EU from the very heavy reliance on China. Although that may prove difficult. The EU is also looking more carefully on Chinese investment in critical infrastructure in Europe. However, as we have seen trade with China is still growing, the “inconvenient truth is that with its still growing importance for European companies, the Chinese Market as such has become strategic.” Just take Germany, where export to China for the 30 largest companies in the German DAX account for 15% of their exports. According to Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft: „Deutschland ist auf der Exportseite anteilsmäßig deutlich stärker von China abhängig als umgekehrt: 2,7 Prozent der deutschen gesamtwirtschaftlichen Wertschöpfung und 2,4 Prozent der Gesamtbeschäftigung sind vom Export nach China abhängig. Bei China sind es dagegen nur 0,5 und 0,6 Prozent.“ Any risk of decoupling would therefore seem to weigh more heavily than the still timid efforts in relation to de-risking. In relation to the U.S. trade relations with the EU risk souring for other reasons. The recent U.S. Inflation Reduction ACT (IRA) represents an attempt to boost manufacturing in the US and diversify supply chains away from reliance on China. An example: “The bill mandates that, to qualify for IRA subsidies, EV [Electric Vehicles] products must be assembled in north America – 50 per cent of the final product calculated according to its value at first, subsequently increasing by 10 per cent every year after the bill is implemented.” Some parts of IRA may lead to collateral damage in trade relations with Europa. According to the Council on Foreign Relations “The EU’s immediate response to the IRA has focused on seeking exemptions from the discriminatory clauses. It has attempted to do so by using the threat of a counter-subsidy package as leverage, while accusing America of betrayal and even war-profiteering.” This might of cause be problematic as it may lead to counter reactions from the U.S. But given the size of the European exports the IRA certainly represents a problem for Europe. It remains to be seen how the problem may be solved. What is important in relation to the discussion here is that the U.S. enacted the IRA without regard for European interests. This has also happened in the U.S. attempts to make sure the China cannot get access to certain products deemed critical for China’s efforts to reach and perhaps surpass the U.S. in important areas. Since 2019 the U.S. has put pressure on The Netherland’s government in order make sure that the ASML company (Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography?) cannot export its more advanced systems to China. In July 2022, it was reported that Washington has pressured the Netherlands government to take the campaign against China to a new level, with attempts to further limit ASML’s engagement in China. ASML has near monopoly on the design and manufacture of EUV (extreme ultra violet) lithography machines that are used to print the ultrasmall, complex designs on microchip wafers, part of the process to produce leading edge sub 10 nanometre chips. Today’s striving is for 3 and 2 nm. In 2022 ASML CEO Peter Wennink said that the company had “already surrendered” to the U.S. in 2019 when it stopped selling its most advanced lithography machines to Chinese firms. Now it seems that there is U.S. pressure on other European companies to curb the export of products to China that are essential for chips production. The German companies Merck KGaA and BASF producing chemicals important for chips production would be affected by such export curbs. What we see is a Europe so dependent on the U.S. strategically, that it will just have to accept and follow the U.S. attempts to decouple from China, even though it may hurt trade and certainly not be in Europe’s best interest. No European defence autonomy In an interview with The Economist in November 2019 Emmanuel Macron declared: “What we are currently experiencing is the brain death of NATO. Europe is standing on the edge of a precipice.” Macron’s harsh comment may be seen as a wake-up call to the rest of Europe. Europe must begin to think of itself as a geopolitical power, or it will “no longer be in control of its own destiny” Macron argued that Europe should gain “military sovereignty” and open a dialogue with Russia. Failing to do so would be a great mistake. Wise words but no one listening. That was 2019, now the time for dialogue with Russia has passed, and NATO has been brought back form the dead, but the issues raised by Macron have not disappeared. In fact, they have become even more important. Today, Europe, understood as the EU and the European members of NATO, do not seem to be able to think and act on their own. They tumble headlessly along in the U.S. and Zelensky slipstream, prodded frequently by Zelensky’s and Kuleba’s sharp demands for more action, and more weapons to serve the purpose of peace. The previously highly praised efforts of Chancellor Merkel searching for peaceful solutions in the Ukraine conflict, her friendly relations with Putin and the German “Wandel durch Handel” approach to relations with Russia, are now seen as having failed miserably. Jubilant Europeans greeting President Biden’s “America is back” apparently also jumped with alacrity into what is essentially an American proxy war against Russia, fought out in Ukraine. Why does Europe accept to be caught in the U.S. slipstream with no apparent independent strategy and ideas of its own? What are they going to do in relation to a Russia that won’t just disappear as a result of the war, but might get even more belligerent? “The EU and member states have thrown several longstanding policies overboard and taken steps that under normal circumstances would have met with strong opposition from various corners. These include decisions for the EU to finance for the first time the delivery of lethal weapons to a third country; to boost its defence cooperation in the face of new threat perceptions; to send (somewhat mixed) signals of openness to EU membership for the bloc’s eastern neighbours after years of enlargement fatigue; and to trigger, also for the first time, its 2001 Temporary Protection Directive, granting temporary residency to Ukrainian refugees. (reliefweb.int). https://reliefweb.int/report/world/war-ukraine-raises-new-questions-eu-foreign-policy European countries suddenly find it important to fulfil their promises to NATO, something Trump could not get them to do. Now, new expansive defence plans and budgets are seen as more important than almost anything else. Still, one wonders if Europe really wants to contribute to an escalation in a U.S. proxy war to defeat the Russians, given the dangers of a Russian escalation. Fanning the flames of the proxy war in Ukraine with more and more weapons and engaging in sanctions that in the end may hurt the Europeans more than Russia? In the near future Europe may have to decide whether to follow and contribute to a U.S. involvement in a continuing proxy war with Russia or even a far-off war with China over Taiwan. Suddenly Macron’s question to Europe seems very important: “Is it in our interest to accelerate on the Taiwan issue? No. The worse thing would be to think that we Europeans must become followers on this topic and take our cue from the U.S. agenda and a Chinese overreaction.” Macron instead talks of the possibility of Europe becoming super power with its own stance in world affairs within a few years, if the world is not in turmoil before that would be possible. This raises two serious questions. First does Europe have choice now or in the near future to take an independent position in relation to U.S.? Would it be wise and possible not to follow the U.S. in a war with China over Taiwan in a near future? Secondly would it be possible in a more distant future to achieve a position as a kind of third and independent power in between the present U.S hegemon and the rising Chinese hegemon? In relation to first question the discussion in the first part of this essay clearly indicates that Macron is right. It would certainly be wise first of all to try to prevent an escalation in the Taiwan strait. But how could an independent European stance lessen the risk a military conflict over Taiwan, when there are growing signs that the U.S. may be preparing for a war with China over Taiwan. Europe might attempt to seek support from far eastern allies like Japan, South Korea and even Australia in a diplomatic effort to prevent war over Taiwan. In fact, they may find some kind of support in Japan and South Korea. Japan being recently worried about the sharply rising mercury in the U.S. these days. In an Economist interview with Prime Minister Kishida Fumio he said: “What must be prioritised is proactive diplomacy.” And proactive diplomacy is certainly needed now. Japan may be wary of China’s hegenomic ambitions, but Kishida Fumio’s words indicate that Japan thinks the American-Chinese rivalry may have got too hot. Japanese leaders have recently called for better communication with China, with Sino-Japanese diplomacy quietly resuming. An article in the “The Diplomat” on South Korea’s view on the prospect of war over Taiwan, also points to a certain reluctance to get militarily involved “There is good reason to think South Korea would limit its support to actions near the low end of the spectrum – strong diplomatic statements, symbolic economic sanctions, and behind-the-lines re-supply of U.S. forces returning from battle – in the hopes of avoiding a direct confrontation with China.” Perhaps a combined diplomatic effort on by Europe (if it could agree with itself), Japan and South Korea might dampen U.S. enthusiasm, lower the mercury and prevent war in the near future. It may be just a vague hope though. For these reasons. The U.S. being almost the sole guarantor for European security and in a similar way for the security of South Korea and Japan, given the U.S. military dominance and ultimately of cause its absolute nuclear deterrence. The U.S. may thus decide to present the allies with a fait accompli, by more or es directly threatening to leave the allies without the protective U.S. umbrella. Meaning that the allies would be under enormous pressure to follow the U.S. into a war over Taiwan. Current European leaders may not even have to be persuaded to follow the U.S. into war over Taiwan. Remember the enthusiastic, almost delirious support based upon on a cocktail of self-righteous moralism and power, that let them stumble along with the U.S. into an unforeseeable but dangerous support for the proxy war in Ukraine. Their shrill voices filled with passion for a what they see as a democratic, albeit very corrupt Ukraine invaded by authoritarian Russia. Taiwan might seem to threatened in a similar way to Ukraine, and being a Western oriented democracy, it would certainly also appeal to European self-righteous moralism. In relation the second question on the possibility for Europe to achieve position as a kind of third and independent power between the U.S. and China in a more distant future like Macron envisaged, the outlook is not good. Europe is not united and does not have a singular overriding view of Europe’s role in the world and is certainly not united in the belief that it might become an autonomous superpower standing between the U.S. and China. It might only see itself as a kind of moralistic “arbiter” that has a certain precarious economic clout as a consequence of its trade relations, but not enough agreement to wield this power. It also lacks self-sufficiency in vital areas like we have seen, and it will be difficult to achieve anything like self-sufficiency even in the long run. Europe would seem to be destined to be dependent on the rest of the World for a whole range of resources. Although dependencies may shift as a result of for instance a U.S. power game, as we are seeing in relation to energy. One dependence, on say gas from Russia, is just being substituted for another dependence the U.S., the Near East and even Africa. Not even with regard to conventional defence is Europe a major power. Having for a long time relied timidly and cheaply on U.S. conventional forces. With the present risk of U.S. involvement in a war with China over Taiwan, the U.S. may have realised that it has far too much on its plate to be able to allocate forces both for Europe and in the Pacific. US may turn attention and weapons towards the Pacific, or get tangled in internal political conflict which might result in less support for Europe’s defence. With the war in Ukraine and the realisation that the U.S. might prioritise the Pacific, European decisions makers have laid up costly defence procurement programs. But an overall European plan for defence investment is lacking and thus procurement seem rather haphazard, every country just trying to get what is available, which would often be U.S. equipment. Thus, demonstrating once again that Europe is not even able to supply material for its own defence, but have to rely U.S. defence companies, with the minor aberration that Poland is buying South Korean equipment like tanks, while others want missiles from Israel. Ultimately Europe is still dependent on the U.S. for security, especially the deterrence provided by the nuclear umbrella. France may a nuclear force, but it seems reserved for the protection of France, and the UK has a nuclear force, but it’s use may be dependent on the U.S. The German politician Manfred Weber, leader of the Christian Democrats in the European Parliament has recently argued in favour of a Europe having its own nuclear deterrence: „Putins Angriffskrieg zwingt Europa, endlich die eigene Verteidigung in die Hand zu nehmen, zumal die USA sich künftig stärker Richtung Pazifik orientieren dürften. Dazu gehört auch die Frage nach atomarer Abschreckung: Deutschland und Frankreich sollten jetzt darüber reden.“ (Focus). He is still a lonely voice in relation to most of Europe. Germany for instance being more occupied with getting rid of the last vestiges of peaceful version of nuclear power, having just closed its last nuclear power stations. The sorry state of European defence independence The sorry state relates to low overall European expenditure on defence compared to the superpowers. The dependence on the U.S. defence industry for material, and the patchwork of common European defence initiatives. Using data from SIPRI we can compare overall defence spending for the year 2022 measured in billion US $ at 2021 prices. Note that U.S. Depertment of Defence estimates that China’s real military spending may now be around 1.1 to 2 times higher than stated in its official budget. While European expenditure may look high compared to China, it interesting to see to what degree it actually contributes to military defence autonomy for Europe. For years there has been talk of a European Army, although the discussions never got very far, presumable because most European members of NATO would have seen that European defence capabilities would in the end have to rely on NATO and especially of cause its most important member, the U.S. After the Afghanistan withdrawal debacle, where Europe mostly were left out of the Biden administration’s decision making, the discussion of an independent European defence initiative popped up again. In von der Leyen’s State of the Union speech on September 15 in 2021 she mentioned that the EU had begun to develop a European defence ecosystem. She then said “But what we need is the European Defence Union.” Arguing that “that Europe can – and clearly should – be able and willing to do more on its own.” For three reasons: “The need to provide stability in our neighbourhood and across different regions; the nature of the threats we face is evolving rapidly; the European Union is a unique security provider. There will be missions where NATO or the UN will not be present, but where the EU should be.” Explaining why similar ideas had not been realised in the past she touched, perhaps inadvertently, upon the ultimate reason why the European autonomy Macron envisaged cannot be achieved. What is holding a European Defence Union back in her view is “not just a shortfall of capacity – it is the lack of political will.” A lack of will, caused by the lack of unity of purpose and shared strategic outlook among European states.“What should amount to a largely practical and pragmatic effort often descends into an ideological squabble over “strategic autonomy” or national sovereignty. Bureaucratic turf wars erupt between ministries of defense, NATO, and the European Union over roles and responsibilities.” Although Europe spends a substantial amount on defence, it is still less than had been agreed upon, but the war in Ukraine have certainly brought forth a radical change. Former unwillingness to engage in large defence spending programs, has now been substituted for extraordinary programs in many European countries. An EDA (The European Defence Agency) report finds a marked increase in spending on defence equipment procurement and defence R&D in Europe. This has brought to light another European problem related to defence procurement. It has mostly been and still is a chaotic everyone for themselves. Every state initiating big military procurement programs on their own, with almost no real cooperation. Leading just as before to an assortment of different equipment, and by the way presumable to competition between the states in their procurement programs, thus leading to the lack of both efficiency and effectiveness.

“As EU countries tend to extensively implement their defense plans at the national level, only 18 percent of all investment in security programs were conducted in cooperation, a decrease of 1 percent from 2020. In addition, no improved coherence of the EU defense landscape has been visible. The key factors identified as impacting nations’ decision making were primarily nationally defined requirements, followed by achieving NATO targets, and finally EU priorities. Many were said to consider European cooperation approaches as more difficult and time consuming, which ultimately results in them opting for national solutions or non-EU solutions.” (Report from the European Defence Agency). Cooperation is hampered by what has been fittingly called the cacophony problem. Which is a result of “profound, continent-wide divergences across all the domains of national defense policies, most notably threat perceptions.” All states speaking with different voices on at the same time. The problem is so deeply rooted in independent national thinking and decision making that there is certainly no near-term solution. The result is strategic divergence, fragmentation in European procurement, leading to problems with European defence planning and multinational operation. In short Europe defence procurement represent a patchwork quilt of many separate and divergent decisions with regard to procurement. This represents a challenge to multinational operations given the growing complexity of modern warfare. The natural conservatism of military organizations poses a serious challenge for European military cooperation in particular, given the disparities in technology and capability among them and with key allies. A report from CSIS (Center for Strategic and International Studies) describes how a lack of joint procurement led to fragmentation and duplication: “European armed forces suffer major redundancies, with 29 different types of destroyers, 17 types of main battle tanks, and compared to four, one, and six, respectively, for the United States. Some European countries have managed to develop joint platforms in the past, such as the A400M military transport aircraft, the Eurofighter combat aircraft, and the Tiger attack helicopter.” Years of underinvesting in European defence during the long period when Europe slumbered under the U.S. military protection umbrella, led to less focus on upholding a European defence industry able provide at least some kind of Europe autonomy. Programs like the European Defence Fund’s €1.2 billion program for 2023 and the recent EDIRPA (European Defence Industry Reinforcement through common Procurement Act) accompanied by €500 million earmarked to encourage member states to procure defence products jointly, seem timid in relations to the scale of the problems just discussed. We have to conclude that Macron’s idea of having a European defence, independent of the U.S. looks rather farfetched in the light of what we have seen. For a foreseeable future Europe will be damned to be dependent on U.S. military capabilities and as said before on U.S. nuclear deterrence. A strategic compass with no magnetism Maybe the EU had finally realised that there is need for some kind of strategic goal for Europe when they adopted a so-called “Strategic Compass for Security and Defence” in March 2022, finally awakening to the dangerous strategic challenges facing Europe. According to Borell “The Strategic Compass is setting out concrete actions in the following four work strands so that we: Act more quickly and decisively when facing crises; Secure our citizens against fast-changing threats; Invest in the capabilities and technologies we need; and Partner with others to achieve common goal” Borell expresses his “hope that this Strategic Compass will help us, finally, face our security responsibilities, in front of our citizens and the rest of the world. If not now, then when?” In the face of all the obstacles we have listed, this compass may just have too little magnetic force to assure unity. “The elephant in the room” key problem for European autonomy Macron may be wise in wishing for greater European independence, but like we have seen in other areas there is no real European agreement and certainly no unity of purpose that would be an absolute precondition for realising European defence autonomy. Explaining why similar ideas had not been realised in the past Ursula von der Leyen perhaps inadvertently touched upon the ultimate reason why the European autonomy Macron envisaged cannot be achieved. In relation to the failed attempt to create European Defence Union von der Leyen argued that reason is “not just a shortfall of capacity – it is the lack of political will.” Here we actually find the “the elephant in the room” key problem to any attempt to create a solid European autonomy, whatever aspect of autonomy one may think of. Europe is not able to act as one for this reason: European countries are still not able to achieve the necessary overall agreement on Europe’s role in the World, or on an overall strategic vision. This may also explain why Europe as such does not have any authority able to make decisions on behalf of what would have to include the majority of European states. Instead, Europe must rely on achieving a kind unity in action on single issues often belatedly and full of compromises. For these reasons, it is impossible to envisage comprehensive autonomy in any of the areas discussed in this essay. Macron’s talk of a third superpower between in between the U.S. and China is thus no more than a pipe dream. Compared to the U.S. and China, the EU has glaring lack of decisive leadership able to act with authority, and Europe overall even more so. The EU member states represent a patchwork of different views, with absolute no overall guiding strategic view. No wonder therefore that EU political decision-making on vital issues for Europe and the World is so indecisive, messy and always late. The whole decision-making construction of the EU reflects the lack of unity of purpose. The many presidents in the EU, and especially of cause the president of the EU Commission, by design lacks authority and is filled with comprise and second rate candidates that lack decisive leadership qualities. Not their fault of cause. The whole EU construction is at fault, and for this reason any hope of playing on the same level as the U.S. and China with regard to strategic autonomy is misplaced. This of cause goes also for Europe as a whole. A more strategic autonomous for Europe would thus only be possible with less autonomy for member states along with the necessity of having a much more authoritative political structure and leadership. Unless that were to happen European strategic autonomy is only vague swirling bluish wisps of utopian smoke. Unless that is, deadly external threats threaten all of Europe in a similar way. If this happens, decision making may become united and effective, albeit probably always too late. Furthermore, the present moralism and genuflection to an ideology of values also makes Europe impotent to influence what happens in the World. With more realism and a view to what is in Europe’s best interest Europe might be able to find a way to balance between the U.S. and China. Not really as an autonomous superpower, but as someone good at highlining, or perhaps less dangerous “slacklining,” constantly trying to keep the balance. Perhaps James Cleverly, Britain’s Foreign Secretary, in a recent speech gave cause for some optimism. In relation to China, he said "It would be clear and easy - and perhaps even satisfying - for me to declare some kind of new Cold War and say that our goal is to isolate China." But he then argued that it would “be a betrayal of our national interest and a wilful misunderstanding of the modern world.” Isolating China would be wrong as “No significant global problem - from climate change to pandemic prevention, from economic stability to nuclear proliferation - can be solved without China." If Europa as such began to emphasise similar attitudes it might represent the first very small step towards avoiding falling into the trap Macron feared, “The trap for Europe would be that, at a time when it is achieving a clarification of its strategic position, … it would be tangled up in world destabilization, or crises that aren’t Europe’s” Curio addendum: As an aside one may wonder how ChatGPT answers a question relating to alignment of countries with the U.S. Question: Was alignment with say the US really based on the countries´ own volition? The full ChatGPT answer: The decision of a country to align itself with the United States, or any other country, is not always based purely on its own volition. In many cases, the alignment of a country with a particular power is influenced by a range of factors, including historical ties, economic interests, and strategic considerations. During the Cold War, for example, many countries aligned themselves with the United States or the Soviet Union based on a range of factors, including ideological considerations, military alliances, and strategic interests. In some cases, countries may have been pressured or coerced into aligning with a particular power through the use of military force, economic sanctions, or other forms of coercion. However, it is also important to note that countries may also choose to align themselves with a particular power based on their own perceived interests and strategic goals. In some cases, the alignment of a country with the United States may have been driven by a desire to counterbalance the influence of a regional rival or to gain access to economic and military resources. Ultimately, the decision of a country to align itself with a particular power is a complex one that is influenced by a range of factors, both internal and external. Not really answer. Just a presentation of possible considerations related to the question. |

Author

Verner C. Petersen Archives

May 2024

|