|

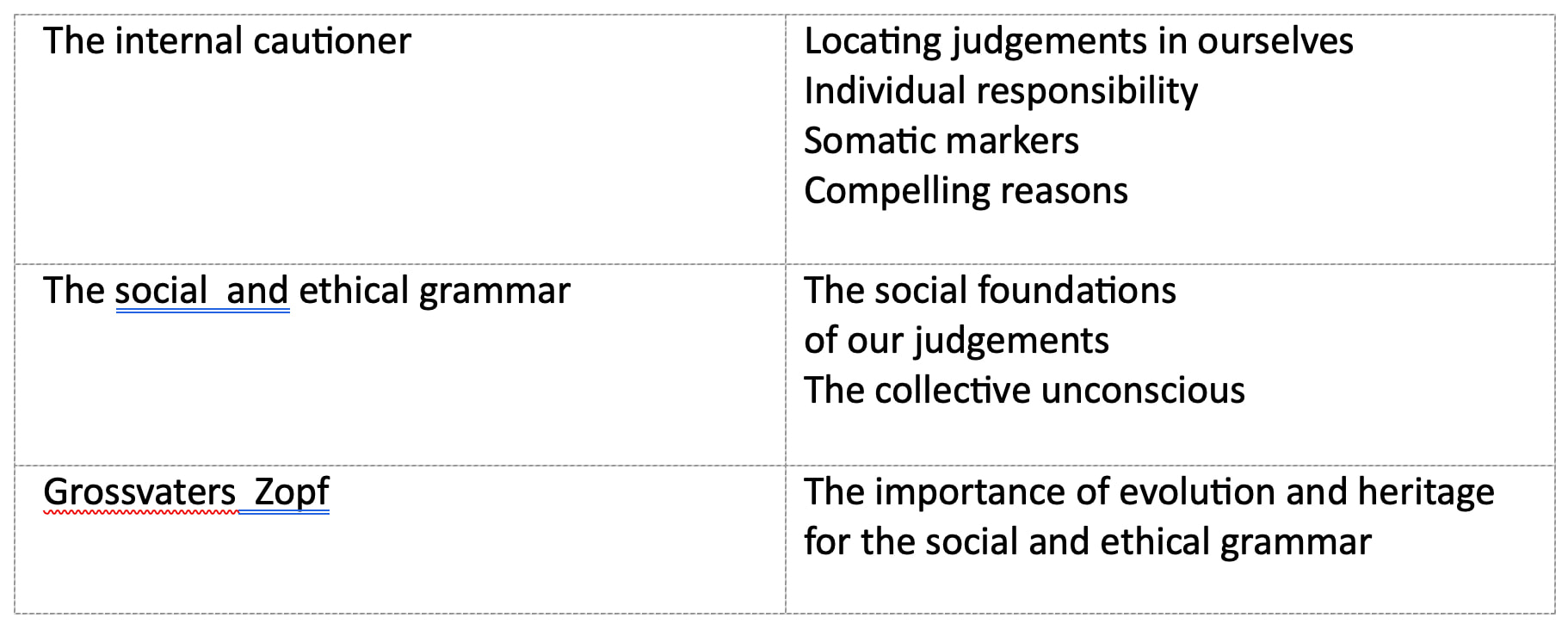

Wahrlich, die Menschen gaben sich alles ihr Gutes und Böses. Wahrlich, sie nahmen es nicht, sie fanden es nicht, nicht fiel es ihnen als Stimme vom Himmel. Werthe legte erst der Mensch in die Dinge, sich zu erhalten, - er schuf erst den Dingen Sinn, einen Menschen-Sinn! Darum nennt er sich "Mensch'', das ist: der Schätzende … Wandel der Werthe, - das ist Wandel der Schaffenden. Immer vernichtet, wer ein Schöpfer sein muss. Friedrich Nietzsche “Also sprach Zarathustra” HABITS OF THE MIND Suppose for a moment that making a moral judgement is in some way analogous to recognising a face of a person we knew a long time ago. It may seem strange, but please humour me for a moment. It is rather difficult to know the particulars of what makes us recognise a face that we have never seen in exactly this shape before, perhaps because it is 20 years ago that we saw this face last. We are of course presuming that the person in question does not have some very recognisable feature, like a large mole on the tip of his nose. That would give the game away. We are also able to recognise a whole range of facial expressions, although we may not be able to state the particulars of this process. We just do it. If routine moral judgements are made in the same way, we may not be able to give a lot of reasons for our judgements; we may just be able to state that we feel that this would be the right or the wrong thing to do. When asked why this would be right or wrong, we are unable to appeal either to universality, utility or any other criterion. To us it might be evident almost in the same way that it would be evident that this is the face of Peter. A simpler example might involve discerning between a genuine smile and a faked smile. I suppose that almost everyone would know immediately what I mean by a genuine and a faked smile. Not that most people know anything about the muscles of face; we just say that a faked smile would be revealed by the eyes. Damasio has the story of the particulars. A smile of real joy requires the combined involuntary contraction of two muscles, the zygotic major and the orbicularis oculi. We can wilfully control the first while the orbicularis oculi is beyond wilful control. Normally we would not be able to explain that, but we recognise the effect. We see the smile of joy. In other words, we are able to recognise faces, genuine smiles, faked smiles, chairs, sexual harassment, and make judgements on things and behaviours violating our moral sense. To argue why this is possible we have to show the plausibility and importance of a tacit and ineffable foundation of our value judgements. We begin with the tentative list of sources for the habits of the mind outlined in this table: THE INTERNAL CAUTIONER Some inside cautioner warns me to stay in my place in spite of the urge I feel, like the cautioner in Baudelaire’s poem: Each man who’s worth the name must know A yellow Serpent is at home Within his heart, as on a throne, Which, if he says: ‘I want!’ says: No!’ Written rules and explicit threats of external sanctions prohibiting or limiting a certain kind of behaviour would never be able to equal the internal tacit cautioner saying “no” to me. Is this perhaps the only place where we can locate our much sought after individual sense of responsibility? We shall see. Perhaps we may glean some insight on this internal cautioner by employing Damasio’s concept of somatic markers. Instead of committing the mistake of believing that we act as advanced electronic calculators when faced with an ethical dilemma, Damasio almost follows Dennett in believing that our minds rapidly create sketches of multiple scenarios of possible responses and actions. In the case of an ethical dilemma, a silent patron of our minds may help us produce and evaluate the multiple fleeting sketches of possible decisions and actions, before we reason consciously about what we do. This production and evaluation seem to happen before any conscious reasoning. It comes preselected to our conscious mind. Preselected perhaps with the aid of somatic markers. A somatic marker may force “attention on the negative outcome to which a given action may lead, and functions as an automated alarm signal which says: Beware of danger ahead if you choose the option which leads to this outcome. The signal may lead you to reject, immediately, the negative course of action and thus make you choose among other alternatives.” The important lesson we can draw is that a somatic marker may kick in, before any conscious reasoning about the problem. This marker represents a more sophisticated version of what we may call gut feeling. The unpleasant feeling that shows that we may not be comfortable with a certain decision or action. This also seems to be the reason for the name ‘somatic marker’. ‘Soma’ for body, or bodily reactions and ‘marker’ because it marks the sketches of the mind. A somatic marker may act more subtly than that, no queasy feeling in the stomach is necessary, the uneasiness may show itself in a bias that we are unaware of. It may reveal itself in no more than the expression: “I feel it would be right.” This fits well with the way somatic markers are supposed to be created. “When the choice of option X, which leads to bad outcome Y, is followed by punishment and thus painful body states, the somatic marker system acquires the hidden, dispositional representation of this experience-driven, non-inherited, arbitrary connection.” It does not have to be punishment; many diverse experiences such as displeasure, acceptance and praise may of course lead to the creation of somatic markers, which are activated automatically before and during our reasoning process. Somatic markers represent special feelings generated by emotions, a conditioned feeling that we have somehow learned, and which guide and restrict our judgements. We may think of them as biasing devices; they do not put us on a kind of autopilot, but subtly guide and restrict us in our judgements as well as in our actions. Somatic markers may be felt when we talk about a certain action giving us a bad taste, or a queasy feeling in the stomach. In ways we cannot individually understand and explain they signify a bias of our feelings, and there is not much we can consciously do about that. Deacon does not talk about somatic markers, but his arguments in relation to the role of emotion in reasoning made us aware of how somatic markers may play a role in reasoning. “Powerful mental images can elicit a vicarious emotional charge that makes them capable of outcompeting current sensory stimuli and intrinsic drives for control of attention and emotion, resulting in a kind of virtual emotional experience.” During our reasoning we may thus be emotionally influenced by the images that are evoked. It is not just any emotion that is allowed to pass through and influence actions. We are talking about conditioned feelings, feelings like embarrassment, shame and remorse. Feelings “acquired by experience, under the control of an internal preference system and under the influence of an external set of circumstances which include not only entities and events with which the organism must interact, but also social conventions and ethical rules.” Perhaps these feelings and markers are also what compel us to act, making us feel that we have to, almost without thinking. The internal cautioner may in some cases urge us to act, in other cases put up a warning sign saying: “No way!” Any reference to Kantian principles or any calculation of pros and cons will not be enough to compel us to act. This may bring us an accusation of subjectivism. Not so, there might be a kind of non-subjective common foundation for the biases and somatic markers that we possess, without being able to state explicitly what these biases are. THE SOCIAL ETHICAL GRAMMAR We shall argue that moral judgements are made according to what might be seen as a social and ethical grammar. Here we use both terms, social and ethical, because we want to underline the social part of this grammar, realising of course that certain parts of the grammar may be social, but not necessarily have anything to do with ethics. Table manners, dress codes and so on come to mind as something that may belong to a social grammar, but have little relevance for ethics and morals. Perhaps our concept of grammar may have more in common with Wittgenstein’s “Sprachspiele.” In Philosophischen Untersuchungen he writes “Grammatik sagt nicht, wie die Sprache gebaut sein muß, um ihre Zwecke zu erfüllen, um so und so auf die Menschen zu wirken. Sie beschreibt nur, aber erklärt in keiner Weise, den Gebrauch der Zeichen.” A small example from Cosmides and Toby may demonstrate how such a grammar might work. We have to consider two sentence samples: 1 If he’s the victim of an unlucky tragedy, then we should pitch in to help him out. 2 If he spends his time loafing and living off others, then he doesn’t deserve our help. Contrast this with: 3 If he’s the victim of an unlucky tragedy, then he doesn’t deserve our help. 4 If he spends his time loafing and living off of others, then we should pitch in to help him out. I suspect that most readers would find nothing wrong with sentences 1 and 2, while sentences 3 and 4 may seem rather odd or disturbing. Why should anyone want to say something like that? In a sense sentences 3 and 4 are as good as the first two sentences. What is wrong is that sentences 3 and 4 state something that seems unjust to our moral senses, perhaps leading to us to blurt out: “This wouldn’t be fair would it?” Presumably most people intuitively see these sentences as stating something that would be unjust. It would be seen as evident, not as something that had to or could be explained. What is happening may be analogous to what is happening when we recognise a face. We cannot tell what particulars are involved, we just recognise it. It may be in this sense that the two sentences violate an ineffable grammar of ethical and social reasoning. Our biases and somatic markers may be based on a shared social and ethical grammar, which may reveal itself in the feeling that there is something odd about sentences 3 and 4. This is the kind of grammar that may lead us to nod approvingly at sentences 1 and 2, and to feel that there is something strange about sentences 3 and 4. It is a grammar that consists partly of overt rules and examples and partly of covert norms and predispositions, making us able to judge and act in relation to specific cases, almost in the same sense that we are able to construct sentences, without looking up explicit rules or making prolonged calculations. “In the study of reasoning, a grammar is a finite set of rules that can generate all appropriate inferences while not simultaneously generating inappropriate ones. If it is a grammar of social reasoning, then these inferences are about the domain of social motivation and behaviour; an ‘inappropriate’ inference is defined as one that members of a social community would judge as incomprehensible or nonsensical.” Or, may we add, unethical. We assume that a social grammar would be characterised by being: • layered, and contingent, not derivable from simple principles; • shared as a collective conscience, internalised by individuals; • generative and non-determinative. Layered We presume that parts of the social grammar may be found in the explicit rules regulating and limiting the behaviour of people in a community, all the way from the Declaration of Human Rights, parts of national constitutions, via specific laws against corruption or sexual harassment, to family and personnel policies. These rules would seem to represent a surface layer of explicit ethical norms that either have or can be given a written expression. The explicit rules of the surface layer would then represent the upper tip of a whole root-like structure of ethical norms, experiences and knowledge. When we discuss the foundations of these norms, we are in a way attempting to follow the reasoning down along the roots, trying to understand the foundation of these rules. On the intermediate level we might find vaguely defined expressions like fairness. On the next level we argue that ethical judgements apparently involve much more than following written ethical codes and laws regulating behaviour. It involves as we have seen an internalised ethical grammar, or a set of tacit norms, and a certain level of knowledge. At this intermediate level judgements seem to relate to some vaguely defined norms that we can only talk about in a roundabout way. They are not usually written down, but are expressible in a general way, like fairness or justice. They may also be likened to the tacit rules of a moderately skilful chess player, who according to Black is “guided by memories of his own previous successes and failures and, still more importantly, by the sifted experience of whole generations of masters. The accessible tradition supplies defeasible general maxims, standardised routines for accomplishing particular subtasks, detailed models for initial deployment of pieces ... and much else.” We can think consciously about the norms and values, and they seem to be part of our common sense. Maybe this is the level where we can locate the philosophical discussions of ethics and instances of ethical appeal. Maybe this is the level where we can find expressions like: “It is in the interest of all ... that this kind of behaviour is not condoned.” At this level we are still able to give some kind of reason for the judgements we make, although the arguments may be rather philosophical. An even deeper level would represent the really unconscious layers of the mind, containing ethical norms and feelings, inclinations and emotions that belong to the collective unconscious. In our conception we see no need for complete hierarchical consistency, only an overall coherence, anchored in decentralised way in the collective unconscious. There is no single overriding principle either Kantian or utilitarian, only a tacit consistency between a multitude of possible practical judgements on the surface and the deeper layers; like a linguistic grammar a social grammar is in no need of a single overriding principle. What we have instead are mutually supporting decentral elements. According to our model Kant and Mill may respectively have distilled as it were some of the general elements that seem to belong to reasoning on the basis of these layers, but their ethical principles cannot be used the other way round to determine practical ethical judgement. This would be an attempt to make them into first principles, first principles that would tear up a much more subtle decentralised structure, in effect making them sterile and impotent as principles for judging concrete cases. Shared and silent Angell argues that every group of people have to share something in the nature of moral order. “People cannot work together without overt or tacit standards of conduct corresponding to their common values.” He argues that even a family would not be held together solely by mutual affection; there has to be some moral integration, consisting of shared views of what it means to be a family and what is proper conduct for family members. Perhaps this may represent what Durkheim has called the collective conscience of a society. Here we want to emphasise something else, something we might for want of better expression call the collective unconscious. The unconscious part of this consists in “everything of which I know, but of which I am not at the moment thinking; everything of which I was once conscious but have now forgotten; everything perceived by my senses, but not noted by my conscious mind; everything which, involuntarily and without paying attention to it, I feel, think, remember, want, and do; all the future things that are taking shape in me and will sometime come to consciousness: all this is the content of the unconscious.” The unconscious may partly be personal, partly shared and thus collective. We want to emphasise the collective part of the unconscious, the part that is shared across a community of individuals, and owes its existence not to the single individual but like a linguistic grammar is shared collectively. A community would expect that the grammar they are using would be shared by everyone else in the community, so that when they act according to the grammar, they can count upon the other members of the community. We must have this implicit faith in judgement and actions of our fellow human beings or we would have no community. “A social organism of any sort whatever, large or small, is what it is because each member proceeds to his own duty with a trust that the other members will simultaneously do theirs.” In fact it is the tacit belief that others will do their part that will help create the fact that will be desired by all. Or as James would have said: “There are, then, cases where a fact cannot come at all unless a preliminary faith exists in its coming. And where faith in a fact can help create the fact …” To use a grammar is to observe and follow a certain social habit, usage or “rule.” “Ist, was wir ‘einer Regel folgen’ nennen, etwas, was nur ein Mensch, nur einmal im Leben, tun könnte? … Es kann nicht ein einziges Mal nur ein Mensch einer Regel gefolgt sein. Es kann nicht ein einziges Mal nur eine Mitteilung gemacht, ein Befehl gegeben, oder verstanden worden sein, etc. – Einer Regel folgen, eine Mitteilung machen, einen Befehl geben, eine Schachpartie spielen sind Gepflogenheiten (Gebrauche, Institutionen).” There are social limits to the values that individuals and groups can hold if the community in question has to survive as a community. This is a problem of coherence. Different groups and communities may have different grammars, but only to a certain degree, and like Cosmides, Tooby and Aitchison we assume that there are elements of a universal grammar in all the local grammars. We may guess that there has to be a certain universality in every community of people. Examples of widely held grammars or collective consciences might be the protestant ethic described by Weber as characterising a certain period in Western capitalism, while Confucianism might point to some of the basic elements of an Eastern grammar. Generativity We do not have to learn a preconceived set of sentences by heart, we form our own sentences. As long they are formed according to more or less tacit demands of the grammar, they may be regarded as instances of well-formed sentences. We can form sentences never heard before, and still they would be recognised as applications of the grammar. In a way it may be like playing according to well-understood general rules of a game. They define the game, but they do not define the individual actions. This shows the general generativity of a linguistic grammar. A generative grammar is thus a set of explicit and tacit rules that can be used to create new sentences, which would be regarded as well-formed and grammatical in a given language. A generative grammar will not allow the generation of sentences that are ungrammatical, meaning that they would be regarded as ill formed in a given language. Practices showing up in social habits, habitus, rituals and so on are all part the imprints left in us of the evolution of man and community. GROSSVATERS ZOPF Writing about our virtues, Nietzsche looks to their origin. He asks “What does it mean to believe in one’s virtue?” and whether this “isn't this at bottom the same thing that was formerly called one's "good conscience," that venerable long pigtail of a concept [Begriffs-Zopf] which our grandfathers fastened to the backs of their heads, and often enough also to the backside of their understanding? So, it seems that however little we may seem old-fashioned and grandfatherly-honorable to ourselves in other matters, in one respect we are nevertheless the worthy grandsons of these grandfathers, we last Europeans with a good conscience: we, too, still wear their pigtail.” We still carry our grandfather’s pigtail of virtue on and especially in our heads. One may wonder whether Nietzsche already had a notion about the importance of amygdala for emotions that we cannot explain and now perhaps even virtues. We are looking for the origin of the social grammar. Perhaps this pigtail of history and evolution shows where the social grammar originates, in the history of man’s development, in the evolution of man and of community. Parts of our social grammar may consist of remnants of values that evolved in periods during the evolution of communities that we have either no evidence or only very circumstantial evidence of. The deepest and most durable elements of our social grammar may very well be a result of this evolution, all of it. Some of our fundamental notions of and feelings about morality will have origins hidden so deep in our evolution that we can only transmit them from generation to generation as habits and inclinations we are not even aware of, and if we are, then we cannot give any explanation for them. We may of course guess as to their possible purpose and function, but in fact it might be even more difficult to explain why we should have certain moral dispositions than it would be to explain why we have the morphology that most human beings have today. Why this relation among the different parts of our bodies and not another? Why this number of fingers, this placement of the eyes, the larynx and so on. Such a question might even sound curious, but a similar question with regard to our basic moral dispositions would sound even curiouser. Might we not be fairly confident in assuming that, although many other configurations might have been possible, the configuration that we have is consistent and important to a degree that we may only begin to comprehend. It is not arbitrary; there is a “reason” but we may never be able to comprehend it. The “reason” has been produced and reproduced during man’s evolution, transmitted from generation to generation, leaving an echo in somatic markers, deeply held convictions and in cultural habits. This reason is not transcendental, is not given a priori and it does not represent a decree from God. It is located on the earth, in man. Like God and the transcendental this reason has been produced by man, but we can have no recollection of the process; we may only carry the faint imprint in our feelings and reactions. This does mean that this reason is innate; it may be imprinted in other ways, and if it is hardwired in any sense it might be in the neural network of our brain. This reason acts as the field of an invisible magnet on iron particles, orientating us into patterns or into grooves that we cannot comprehend. These patterns, grooves or imprints are ineffable and tacit, in the same way that a part of our knowledge is. We only experience the feelings, not the reasons, not the explanations. These imprints may be so much part of what it means to be human that we cannot really think about them or question them; they make themselves felt in the way they influence our thoughts. The elements of the grammar we become aware of may likewise be regarded as “natural” intuitions, natural in the sense that we suppose they are shared by other human beings. Perhaps we assume that we may be able to learn an infinite number of social grammars, but the one we learn is the one characterising our community. In this way social and ethical grammar come to be shared among the members of a community. Like the linguistic grammar it is neither freely chosen nor arbitrary, but the result is that “human thoughts … run along pre-ordained grooves.” It is in these “natural” imprints we locate the roots of those intuitions that philosophers have grappled with and attempted to anchor in first principles; attempts that we have to regard as rather futile in the light of our theses. If the imprints are not a result of transcendental a priori categories, or God-given commands, or innate dispositions, they have to stem from somewhere else. The imprints we are talking about seem to exist independent of any specific individual, but where do they originate, and what has kept them alive during the evolution, if they are not located in the genes? The answer is of course the values instilled and transmitted from grandfathers to fathers, to sons and to their sons; the values instilled by a community of grandfathers – and grandmothers. This points to the importance of symbolic representations, of rituals, of religious convictions and of ideologies This would mean that repetition of rituals, the meaning of which might elude us, would by the sheer repetition lead an individual subject to these repetitions to absorb the general aspects of the social grammar, without being able to explain what they are. This represents once again a parallel to the first acquisition of linguistic grammar. In a sense it can be said that we learn the grammar by repetitive use of a language based upon this grammar. We seem able to generalise from this repetition, but we may never have understood explicitly any of the fundamental rules underlying our use of the language. We do not learn the grammar directly by being taught social grammatical rules; we learn it indirectly from people who use it, by imitating, by approval and disapproval, expectations, praise, and so on.66 The importance of ritual is also underlined in Bourdieu’s writings. His concept of habitus represents a set of dispositions that disposes an individual member of a community to judge, act and react in certain way. “Symbols are the instruments par excellence of ‘social integration’: as instruments of knowledge and communication …, they make it possible for there to be a consensus on the meaning of the social world, a consensus which contributes fundamentally to the reproduction of the social order. ‘Logical’ integration is the precondition of ‘moral’ integration.”68 Social inculcation through participation in a collective practice produces habitus “that are capable of generating practices regulated without express regulation or any institutionalized call to order.” Practices showing up in social habits, habitus, rituals and so on are all part the imprints left in us of the evolution of man and community. This essay is based upon an excerpt from my book “Beyond rules in society and business” Edward Elgar 2002 & 2204. Was überzeugt mich denn, daß der Andere ein gewöhnliches Bild dreidimensional sieht? – Daß er’s sagt? Unsinn–wie weiß ich denn, was er mit dieser Versicherung meint? Nun, daß er sich darin auskennt; die Ausdrücke auf das Bild verwendet, die er auf den Raum anwendet; sich vor einem Landshaftsbild benimmt, wie vor einer Landschaft, etc. etc. Ludwig Wittgenstein Hog futures have declined in sympathy … The subtitle is taken from a radio announcement in DeLillo’s book White Noise.1 It made me wonder how much knowledge is taken for granted.2 Most educated people at least in the developed countries would probably have some gist of understanding what this announcement could mean and be able to attach some sense to it. A child listening to an announcement like this might only understand the expression “hog,” and part of the rest of the expression, which ends with: “adding bearishness to market.” An educated person might understand most, but have some trouble with futures, perhaps having only the vague notion that it is somehow related to the stock exchange, to certain television programmes and special pages in the newspaper. “Bearishness” might also give trouble, but with all the interest in prices of shares and derivatives, he or she might even have an understanding of that. To those selling and buying futures the announcement is immediately understandable, although perhaps they wonder with what the futures have declined in sympathy. The announcement might lead them to take action in reaction to the news, selling their futures, whatever. To a farmer in the hog business the announcement might mean something else, and might even galvanise him into action, perhaps leading him to make decisions resulting in long-term changes in the production of hogs. There are many levels of understanding, and it would seem that in order to understand the announcement the recipient would have to draw on a vast storage of preconceived notions. The announcement may be compared to a coded message that can be picked up by a recipient with the right decoding apparatus; not only an apparatus that would make it possible to make sense of the phonemes. The apparatus would have to consist of stored knowledge that would make it possible to understand the meaning of expressions like hog, hog futures, decline, sympathy, bearishness and market, and the possible relations between these expressions. The argot of the stock exchange demands an implicit understanding with the recipient, because such an announcement is usually not accompanied by a very detailed explanation of what hogs, futures and sympathy means, or indeed what the whole expression might mean. Some sort of taken-for-granted knowledge is necessary in all human communication. There is never enough information in the expressions we use to make them self-explanatory.3 Context and prior knowledge are necessary. This goes to show that our everyday language rests upon a lot of built-in tacit assumptions or we would not even know what it means when someone says: “It is raining.” In order to understand common expressions we have to possess some kind of taken-for-granted knowledge. Usually we do not have to think about this knowledge, it just seems to be readily available. Knowing more than one can say … Take a look at a skilled mountain biker, picking his way down a difficult slope. Does he know what he is doing? In a particular sense certainly, or he would not be able to stay on his bike. In another sense perhaps not. He may not be able to explain what he is doing very well. He is speeding down a complicated cross-country track without really thinking about what he is doing, letting some part of his mind and body adjust to the varying conditions without consciously thinking about what should be done. If he had to think of how a sudden obstacle could be tackled, he would either react too late or attempt an evasive manoeuvre bound to result in a fall. This I believe to be a plausible result taking into account the time it takes for the obstacle to register in the brain, the time to think consciously about the problem and then react by transmitting messages to various parts of the body, causing muscles to contract, making the knees bend, and the body sway this way or that, ultimately shifting balance and so on. He seems to have the problem well in hand. In fact it is as if he is thinking with his hands or perhaps the whole body, without being involved in too much conscious thought. Libet’s experiment in the 1980s confirms at least part of this supposition. Libet made experiments in which he asked volunteers move their hands whenever they wanted to, while he was measuring the activity of the test subject’s brain. It turned out that brain impulses associated with the movement of the hand began a few hundred milliseconds before the test subject reported any intent to make a movement. This would mean that the “voluntary action did not originate consciously.”7 In the case of the skilled mountain biker it would seem that part of the brain handles processes and initiates actions independently of conscious thought. This seems to happen all the time when we move around, pick up things, write, play an instrument. A special report on this phenomenon in the New Scientist carried the heading: “Don’t look now there’s someone else running your body.”8 In a fairly naïve way this is evidently right, at least for some of our motoric activity; we do not have to think consciously about walking in order to walk, except possibly when inebriated or handicapped in a certain way. We are interested in other aspects though, such as the tacit foundation of our knowledge and judgements. “We say: ‘Take this chair’ and it doesn’t occur to us that we might be mistaken, that perhaps it isn’t really a chair, that later experience may show us something different.”9 But ask someone to describe a chair, and he might get into trouble. When asking this question, or rather asking in Danish for a general description of a stol, typical answers range from “Something to sit on” to “A horizontal plane supported by four legs, and perhaps with a back.” Often the respondents describe a chair as consisting of a seat back, a seat and maybe four legs. This does not characterise all chairs. Some modern chairs have one or three massive legs for instance, in fact the definition found would exclude a lot of chairs. Sometimes chairs might be so strange that we only recognise them as chairs in relation to their surroundings, in their context so to speak. What is important is that we may not be able to give a general description of a chair that would cover all chairs. In order to recognise something as a chair we need a lot of context and some tacit, gestalt-like perception of what we have come to regard as chairishness. Even the chair legs themselves would be impossible to define if they are not seen in relation to the rest. We really would not know what was meant. Legs are only relevant in relation to the rest, to the context. That means we only understand them as attached to chairs, tables, persons or as the legs of a journey. In fact we rely on something reminding us of a gestalt or a patterned definition, perhaps like the way a chess player may describe patterns in a game of chess.12 This means that our concept of what constitutes a chair refers to a whole gestalt-like complex of meanings and interpretations relating to it. Recognising something as a chair fit for sitting on demands more than just recognising the chairishness of the form. Somehow we also seem able to see that a certain configuration has a certain solidity. I am not sure that a chair constructed of single sheets of normal copying paper glued together in the shape of a chair would be seen as chair. Instead it might be seen as a model of a chair, a paper chair, or perhaps as a piece of art. The notion of solidity is presumably based on former experience with the solidity of materials like the ones apparently used for constructing the object, the chairishness of which we are judging. Somehow our skill to judge the ability of a chair to support our weight must be based on all sorts of hands-on experience and tacit calculations that we are unaware of. “The expert performer knows how to proceed without any detached deliberation about his situation or actions, and without any conscious contemplation of alternatives.”13 This fits well with Polanyi, who asserts that it is a well-known fact “that the aim of skilful performance is achieved by the observance of a set of rules which are not known as such to the person following them.”14 This is exactly the level of performance most of us have attained in order to cope with everyday problems. We recognise patterns, pictures, signs, faces and facial expressions without thinking and analysing at length.15 “When we turn our eyes to the face of another human being, we often seek and usually find a meaning in all that it does or fails to do. Grins, sneers, grimaces, and frowns, fleeting smiles and lingering stares, animated faces and poker faces are not merely utilitarian contractions and relaxations of the muscles, but glimpses into the heart of the other – or so it seems.”16 We may understand “fleeting” and “lingering” in relation to facial expressions, but can we explain what the expressions mean precisely? Presumably not and still we seem to be able to read a lot into a facial expression, and make some quick inferences. That facial expressions are understood may be inferred from the reactions we show, looking for dangers if we see fear in another face, reacting with fear if we see angry expression or echoing the knowing smile of someone who sees the same joke that we did.17 We understand words and noises without usually having to think consciously about their meaning. We use a large part of native language as expert performers. We drive bikes, and cars, like expert performers, negotiating every day obstacle courses without much conscious thought. Spending much of our time thinking that some of our fellow rush-hour travellers are morons driving with their heads under their arms. What these examples indicate is that from a certain level of performance we all depend upon some kind of tacit knowledge we are not really aware of. “In some cases, we were once aware of the understandings which were subsequently internalized in our feeling for the stuff of action. In other cases, we may never have been aware of them. In both cases, however, we are usually unable to describe the knowing which our action reveals.”18 In a study of the professional knowledge of nurses Josefson describes a case involving a middle-aged nurse, with many years of experience. In this case a man is admitted to her ward after surgery. After having a short conversation with the patient the nurse concludes that there is something wrong with him, although she cannot put her finger on what exactly it is that has convinced her of that. She calls a doctor, apparently someone with only little experience. He checks the patient’s vital signs and finds nothing wrong. “Later in the day, the patient died, and the post mortem uncovered a complication that could not have been diagnosed by an examination of his vital signs. The nurse’s comment was that she noticed something was out of the ordinary, but could not explain how she had arrived at this conclusion.”20 Previous experience was a decisive factor. Care is central in a nurse’s profession and Josefson mentions that nurses receive theoretical training that inculcates important medical knowledge and information. But this is not enough in a non-routine situation, or as Josefson sees it, when there are unexpected complications. “To deal with this degree of complexity nurses must have the ability to make a reasonable interpretation of events not covered by the descriptions in the rule book. This requires multi-faceted practical experience, through which the information acquired through formal training can be developed into knowledge. That knowledge is built up from a long series of examples which give different perspectives on an illness.”21 One may ask whether we can learn this kind of knowledge. Wittgenstein’s answer is: “Yes; some can. Not, however, by taking a course in it, but through ‘experience’. – Can someone else be a man’s teacher in this? Certainly. From time to time he gives him the right tip – This is what ‘learning’ and ‘ teaching’ are like here. – What one acquires here is not a technique; one learns correct judgement. There are also rules, but they do not form a system, and only experienced people can apply them right. Unlike calculating rules.”22 Recent research on what has been called naturalistic decision making seems to confirm that Wittgenstein had the right idea. In empirical research it has been shown that situated and contextual learning are important for developing expertise, and insight. “[C]ontext provides examples of the conditions that call for actions, the range of permissible actions, and the consequences of actions. It provides opportunities to develop tacit knowledge about subtle features of the situation …”23 “But I have it in my hands” the branch manager of a Danish bank exclaimed after showing the miserable result of an attempt to write a description for making a Windsor knot in a tie. He was frustrated because he knew how to tie his tie into a Windsor knot, but he was not able to make a description of how it was done, even though his hands seemed to know what to do. The tie problem may seem naïve compared with the problems that branch managers and employees of banks have to solve every day, but when they are deciding whether to lend money to a given customer or not, they apparently often find it necessary to go beyond the written instructions, and use knowledge based on experience, vague perceptions and impressions. “It is very difficult just to walk through the swing door and rate a company the first time. One has to have some experience, some knowledge, one has to have some understanding, some impression of what kind of company it is …”26 A branch manager agrees: “As I am often saying, this it not something that one can pronounce, it consists in looking at people, look deep into the eyes, what kind of person is this?”27 Experience, knowledge, understanding, impression, a look deep into the eyes. The terms used are fairly vague. It is not something that can be easily incorporated into a set of guidelines or rules for credit-rating. In fact some of the employees interviewed said that in their opinion they had to go beyond the written instructions, when credit-rating a company. “… much of it is subjective reflections.”28 It is based on a judgement involving written instructions, impressions and inexplicable notions. An area manager talks of the need to be able to get a scent, almost like a tracker dog, when talking to the customer, apparently also listening for the things that are not said. “I am in the habit of saying that one shouldn’t rely on what one is seeing. No, one must use all one’s senses, it has to include Fingerspitzengefühl. The hairs at the back of one’s neck have to bristle, when sitting with someone who is dangerous.”29 Dangerous in the sense that the bank may lose money on that person, if they are persuaded by his business plan. In another bank an employee says that making decisions “has much to do with trust, and this here ‘Fingerspitzengefühl’, also in everyday transactions.”30 Scents, impressions at the tip of one’s fingers, bristling hairs at the back of one’s neck, trust, what kind of knowledge is that? Even CEOs seem to rely on such strange sensations. The CEO of one Danish bank trusts his nose and his guts to give him an idea of how well a branch is run. He talks of relying on structured and unstructured information, from many sources when judging the branches and their managers. All these structured and unstructured impulses decide “whether I have or I haven’t a good feeling in the gut.”31 It would seem that when judging a customer and credit rating a company, bank managers and employees rely on aspects of knowledge they cannot really explain, but which manifest themselves in feelings, impressions and physical signs like bristling hair, conditions of the stomach and taste; in a way thinking with their hands and judging with their guts, as if they possessed some kind of body knowledge. It is important to note though that the impressions and feelings influencing credit rating were apparently used alongside more explicit information and knowledge when making a decision. When stating the reasons for the decisions in writing the emphasis would be on the formal knowledge, on the reference to rules, guidelines and numbers so to speak. In fact one sometimes got the impression that the decision of whether to lend money to certain customers would be based mostly on impressions, experience with the customer and be clothed in more rational terms afterwards, with explicit references to credit instructions and so forth. Bristling hair, Gefühl, gut feelings and taste are translated into terms of formal knowledge and almost algorithm-like reasoning. In this way the decisions are seen as resulting from such algorithm-like reasoning processes, but it is important to remember that these reasons are constructed after the decisions have been made. It would seem that tacit knowledge is important for making professional decisions, but one feels weary using this knowledge in arguments for a certain decision. Instead making it look as if explicit or formal knowledge is the only form of knowledge used in making the decisions. Pointing to something that one cannot put one’s finger on, or using expressions that may sound as if one’s body and not the brain is the place where the ability to make judgements resides, somehow seems irrational and must be covered up in the written reasons given for a decision. Tentative knowledge of knowledge While writing about all these examples and reading and thinking about them at the same time, hitherto strange, unconnected lumps of knowledge about knowledge seemed to coalesce in ways beyond the control of my consciousness. They popped up and disappeared, combined and separated and made new conscious blobs of often fleeting thoughts, like the kind of tentative drafts that emerge, are pushed about, connected and correlated with what one already knows. Often the whole process involves the physical action of finding a theoretical fragment in an article or book, and/or actually the drawing of sketches of what might be termed a semantic network, or in a modern parlance mindmap, looking for relationship, inconsistencies, while the mental sketches change, under the influence of what is now stated on a piece of paper or a computer screen. During one of the sketch drawing sessions, the thought that this could somehow be related to Dennett’s multiple drafts model of consciousness also popped up. “According to the Multiple Drafts model, all varieties of perception – indeed, all varieties of thought or mental activity – are accomplished in the brain by parallel, multitrack processes of interpretation and elaboration of sensory inputs. Information entering the nervous system is under continuous ‘editorial revision’.”34 Dennett’s examples concern perception, for instance visual perception. Most of these multiple drafts or sketches as we call them “play short-lived roles in the modulation of current activity.”35 These sketches, hastily caught on pieces of paper and in elaborate verbal sketches on the computer screen, somehow lead to new sketches, alas often only vaguely related to each other. Even so the sketches seem to contain bigger and bigger lumps, and what emerges is a tentative structure for discussing the different aspects of knowledge in a more systematic way. The tentative typology containing some of the aspects we find important is shown in Table 4.1. Table 4.1 Tentative typology of knowledge What we can say In some of the former examples we have tried to show that one can know more than one can say. Let us now take a look at a kind of knowledge, where one can say what one knows. This knowledge is formal and can be stated explicitly. Declarative knowledge may be represented by statements about facts, relationships, causes and states. An example of a propositional statement might be the expression “the melting point of x-material is y-degrees.” Facts and formal rules used in building radios may represent propositional knowledge. Explicit procedural knowledge describes actions, for instance encoding how to achieve a particular result. An example might be the “Sieve of Eratosthenes,” a simple but tedious method for finding prime numbers.36 Although rather simple for people conversant with mathematics, many may have a problem understanding the meaning of a propositional statement and the Sieve of Eratosthenes may mean nothing to them, which just goes to show that although declarative or propositional knowledge can be expressed very explicitly, it stills demands a kind of implicit or taken-for-granted knowledge. What characterises formal knowledge is that it is overt and almost tangible, it can exist independently of an individual mind, as an expression in a book, or at an obscure Internet address. “The important thing about it is that, being formulated in texts, equations, and the like, it can be discussed, criticized, amended, compared, and rather directly taught. All this is in sharp contrast to the other kinds of knowledge …”40 There is no doubt about the importance of formal knowledge in modern society where most of the knowledge is “outsourced” and located outside us, in all sorts of storages. The question is instead whether the emphasis on formal knowledge erodes the more tacit parts of knowledge that we all depend on, but cannot see or touch or transmit or store in the same way that we can with formal knowledge. I believe that this actually is happening at the moment, as a result of the current emphasis on the explicit and algorithm-like aspects of knowledge. The silent patron In Fodor’s Modularity of the Mind we may find an illustration of the kind of knowledge that does not seem to be formal, although it is stated in a textbook. “Whether John’s utterance of ‘Mary might do it, but Joan is above that sort of thing’ is ironical, say, is a question that can’t be answered short of using a lot of what you know about John, Mary and Joan. Worse yet, there doesn’t seem to be any way to say, in the general case, how much, or precisely what, of what you know about them might need to be accessed in making such determinations.”41 The kind of knowledge that one would need in order to judge whether John’s utterance was meant ironically is difficult to state as formal declarative knowledge. It may represent an informal knowledge that a good friend of John, Mary, and Joan would possess, without really being able to state it explicitly. Most of the knowledge would also be tied to the specific relationships with the involved persons. Someone able to judge whether John’s utterance was meant ironically might not be able to do it if some unknown person had said it; meaning that the knowledge would be situated, except of course for a general ability to discern an ironical tone or lack of same, in an utterance, if we hear it spoken out aloud. In a series of lectures Polanyi in the 1960s tried to work out a whole structure of tacit knowing.42 His starting point is somewhat like ours, that we can know more than we can say. Polanyi shows that there is a certain structure to tacit knowing. Polanyi would say that we attend from the silent perception of the sounds to the meaning of the expression. Or in face recognition, from the silent recognition of particular features of the face to the face. We somehow use the elementary features of sounds or faces to get at their joint meaning. What Polanyi seems to be saying is that we go from particulars to what may be seen as a gestalt. We perceive the particulars of a chair, the legs, seat, back, size, material and so on, without conscious thought and from them we move to the overall gestalt, to the phenomenon, and to the meaning of these perceptions, to the chair. We recognise the chair as a chair without recounting all these particulars, which might be dissolved in even more particular particulars, if we start thinking about what makes up a chair. Now perhaps it is understandable that we have difficulties in giving an all encompassing definition of a chair. Even if we would somehow be able to recount all the tacit from relations, the particulars that give rise to the impression of a chair, we would have difficulty in defining a chair. We tacitly seem to integrate the particulars to a whole, a chair or whatever. “Since we were not attending to the particulars in themselves, we could not identify them.”45 Polanyi draws the conclusion that too much lucidity can in fact be counter-productive. “Scrutinize closely the particulars of a comprehensive entity and their meaning is effaced, our conception of the entity is destroyed. … Speaking more generally, the belief that, since particulars are more tangible, their knowledge offers a true conception of things is fundamentally mistaken.”46 In our chair example this would presumably mean that an attempt to define a chair by recounting all the features, the particulars as it were, would lead to a loss of comprehension of what a chair might be. Perhaps we may also hazard the hypothesis that an attempt to isolate and enumerate the qualities of leadership might lead to a loss of comprehension of leadership and even quality. Somehow those who see different chairs just as chairs must be able to ignore many aspects of the chairs. It is almost as if they reduce or discard information that is irrelevant to the problem at hand without being able to explain how they do it. I wonder whether this ability hints at an important aspect of expertise.48 In fact the breakdown of the world into particulars, legs, seat backs and seats may get us close to a kind self-willed autism. Autistics who have become able to describe their experience reported that they could not make sense of the world. They were focused, nay obsessed with the particulars of the world and these particulars represented meaningless fragments. An article in the New Scientist tells how a sufferer “could not see faces, just collections of noses, eyes and mouths. Words were just strange noises.”49 In other cases it looks as if missing parts are filled in in order to see something. This apparently happens when making sense of sentences that have lost parts in transmission. It may look as if the mind recognises something in a jumble of words or suddenly sees a meaning in an incomplete sentence, usually without much in the way of explicit analysis. With these qualifications in mind it is important to emphasise that attempts to list all the particulars would be futile. On every level and in every profession explicit knowledge rests on tacit knowing. This assertion is important because it flies in the face of many attempts of modern science, including social science and management science. “The declared aim of modern science is to establish a strictly detached, objective knowledge. Any falling short of this ideal is accepted only as a temporary imperfection, which we must aim at eliminating. But suppose that tacit thought forms an indispensable part of all knowledge, then the ideal of eliminating all personal elements of knowledge would, in effect, aim at the destruction of all knowledge.”50 Lumpy knowledge The knowledge of building radios may be distributed over many individual minds, and in books and articles and other repositories of knowledge. When we are building a radio, we are not just assembling bits and pieces of transistors, resistors, diode and so on, but also lumps of knowledge that we cannot explain, like the knowledge of constructing a transistor or a diode.The engineer constructing a radio must somehow operate withthese lumps of knowledge that has to be taken as given. The people designing the cabinet operate with other lumps of knowledge, while those responsible for the production and sale of the radio operate with their specific lumps of knowledge. Going in the other direction, we can see that integrated circuits are constructed and produced using lumps of knowledge that may be found in the construction and production of transistors. This knowledge may again include the lumps of knowledge of physicists working with basic research in different fields. Using the concept of stratified knowledge and hierarchy we can argue that when we are for instance talking or writing, we use knowledge of principles belonging say to phonetics or grammar, without thinking about it. It seems to be a kind of taken-for-granted knowledge that allows us to concentrate on expressing a thought while a more tacit part of our mind takes care of grammar, spelling of words, phonemes and so on, and our hand presses keys that make some filtered version of our thoughts appear on screen, without much conscious intervention from us. Polanyi sees this stratified knowledge as a hierarchy of entities, in which the laws, rules or principles of one level operate under the control of the level above. The voice is shaped into words belonging to a vocabulary, while the vocabulary is shaped into sentences according to the rules of a grammar, and so forth. It is important to note the use of the word “shaped.” This means that the lower level is somehow controlled by the next higher. If the sentences lose control of the words the succession of words may become meaningless. The vocabulary cannot be accounted for by the laws governing phonetics, but in order to talk, the laws of phonetics must somehow be observed. “Accordingly, the operations of a higher level cannot be accounted for by the laws governing its particulars forming the lower level. You cannot derive a vocabulary from phonetics; you cannot derive the grammar of a language from its vocabulary … it is impossible to represent the organizing principles of a higher level by the laws governing its isolated particulars.”51 Knowledge of the radio “shapes” the use of integrated circuits and transistors. A jumble of integrated circuits or transistors would not work as a radio, unless we were very lucky. A chair cannot be derived from particulars of legs, seats, knowledge of materials and so on, because “it is impossible to represent the organizing principle of a higher level by the laws governing its isolated particulars.” Poincare once said that science is built up with facts, as a house with stones. But a collection of facts is no more a science than a heap of stones is a house.52 Emergence Emergence describes the phenomenon that patterns, structures and properties can arise in a way that cannot be adequately explained by referring only to the pre-existing components and their interaction. All the same a radio, as well as a chair, emerges from the local interactions between the already known components. Even so a radio cannot be adequately explained by components like transistors, resistors or other of the components it may include. Emergent patterns are unpredictable and not deducible from the preexisting components. Many social phenomena seem to be a result of emergence, for instance markets, states, communities, cultural and social trends. Somewhat analogous to the example with speech we may presume that the higher levels have to obey the laws of the components, but at the same time the higher level influences the lower level components. The market is a collection of individual agents and behaviours but it also influences the behaviour of these agents.55 Perhaps emergence may in some vague way help us to understand the emergence of new knowledge, beginning with a hunch. Often when attempting to get to grips with something we have a hunch, but what kind of knowledge is a hunch? Apparently it just pops up like a flickering will-o’-the-wisp. When we attempt to follow the weak light, it may turn out to be nothing, or it may be the first step we are aware of when solving a problem or understanding something for the first time. It is as if a hidden and silent patron in one’s mind wants to help, by leaving a clue here and there for me to see, the me that is aware, to pick up and work with. Or by collecting a ready-made solution from some forgotten shelf of one’s memory and leaving it at the doorstep of my consciousness, for me to use, without offering any further explanation. Or by suddenly presenting a new thought in one’s consciousness. While being immersed in an attempt to understand something, for instance tacit knowledge, a new idea suddenly presents itself, a thought one has never had before makes itself heard in the cacophony of thoughts.56 In relation to a question concerning values Polanyi argued that “when originality breeds new values, it breeds them tacitly, by implication; we cannot choose explicitly a set of new values, but must submit to them by the very act of creating or adopting them.”57 Just now I have a hunch that the whole concept as presented here, simple and complex at the same time, is perhaps not entirely convincing. While writing this I was having fragments of several thoughts alternating in the mind at the same time, but one thing is certain I was not thinking about the computer I am sitting in front of, the keyboard, the keys, the work of my hands and fingers, nor the construction of words and sentences according to I know not what rules. This all seems to works automatically without intruding upon the conscious thoughts that I have. This cannot be said to represent a from–to relation in Polanyi’s sense. In fact this seems closer to the thoughts on thinking and knowing in Wittgenstein’s Remarks on the Philosophy of Psychology. For instance when he writes: “Beobachte dich beim Schreiben, und wie die Hand die Buchstaben formt, ohne daß du es eigentlich veranlaßt. Du fühlst wohl etwas in deiner Hand, allerlei Spannungen und Drücke, aber daß die dazu nötig sind, diese Buchstaben zu erzeugen, davon weißt du nichts.”58 In a way I am moving in the opposite direction of the from–to relation, from the to part, the gestalts in the shape of my thoughts, to the from part, the particulars, the hand and finger movements, the words on the screen, the checks of spelling and grammar. My thoughts somehow dissolve in the intricate workings of tacit skills, using the keyboard, tactile and visual feedback, to adjust position and place letters on the screen, where they assemble in expressions that seem to result from my thoughts, although in an odd way they seem to be a little different from what I was thinking. Grammar, syntax and other things may influence what I am writing, filtering out thoughts that are difficult to express or form into sentences. Perhaps this explains why the thoughts appear to come out different than the thoughts I seem to be aware of. Community and heritage At least part of the knowledge that we find in our use of a common language seems to be based upon a kind of shared common or social knowledge. We usually come to think of the same things when we hear certain words in a certain context. “It is raining;” “This is a luxury car;” “I noticed the bike was yellowish;” “It bubbled like boiling water.” In this case we are able to “make inductions in the same way as others do in the world of concerted action.” 61 In some way it would seem that almost all of our knowledge is social. “Luxury”and “yellowish” would seem to be expressions that rely on some kind of common conception of what is meant. Wittgenstein gives support to this idea. “Wenn die Menschen nicht im allgemeinen über die Farben der Dinge übereinstimmten, wenn Unstimmigkeiten nicht Ausnahmen wären, könnte es unseren Farbbegriff nicht geben. Nein: – gäbe es unsern Farbbegriff nicht.”62 But is that not the case for most of what we call knowledge? This community aspect of knowledge also seems to be implied in common sense. Several times we have asked participants in our courses on value-based leadership and management to answer the question: What is “sound reason?” They were also asked whether it was common to all. Many answered that sound reason was individually determined and different from person to person. Others realised that there was an element of community in it, with quiet adjustments to the views of the majority, as can be seen from the answer: “Sound reason can be said to be the decision, that will win general approval with the great majority of a representative sample of a population.”64 Still the majority felt that their sound reason was individual and different from the sound reason of others, perhaps in a curious way this is an impression they also have from the community they are living in and the organisation they are working in. It has become part of their shared and tacit cultural knowledge. One is reminded of a chorus of people shouting: “We are all individuals,” in a Monty Python movie. “Cultural skills include the ability to make inductions in the same way as others in the world of concerted action. It is our cultural skills that enable us to make the world of concerted behaviour. We do this by agreeing that a certain object is, say, a Rembrandt, or a certain symbol is an s. That is how we digitize the world. It is our common culture that makes it possible to come to these agreements that comprises our culture.”65 “Our faith is faith in some one else’s faith, and in the greatest matters this is mostly the case. Our belief in truth itself, for instance, that there is a truth, and that our minds and it are made for each other – what is it but a passionate affirmation of desire, in which our social system backs us up?”66 It is supposed that most of the shared or social knowledge described here would consist of tacit taken for granted knowledge. But knowledge is not only social; in our view it is also inherited from earlier generations, like the language we use, the traditions we observe, the rites we follow, the values we hold, the culture we express. Wittgenstein expresses the idea like this: “Mein Weltbild habe ich nicht, weil ich mich von seiner Richtigkeit überzeugt habe; auch nicht weil ich von seiner Richtigkeit überzeugt bin. Sondern es ist der überkommene Hintergrund, auf welchem ich zwischen wahr und falsch unterscheide.”68 The cell walls of our minds I wonder whether there is another sense in which knowledge might be said to be tacit than the ones we have discussed up until now. Think for instance of standing in the kitchen mixing some ingredients. Often it is important that the mixture has the right degree of viscosity, or fluidness, but when is that achieved and how does one achieve the right viscosity by adding more ingredients? The answer might be that one learns to sense when this is the case almost in the same way that one learns to tie a knot in a tie. But might there not be a something else helping us, perhaps even the mixture itself? To Brown et al. the answer to this question is affirmative. They see problem solving as being carried out in conjunction with the environment, not solely inside the heads of the problem solver. “Instead of taking problems out of the context of their creation and providing them with an extraneous framework, JPFs [Just Plain Folks] and practitioners seem particularly adept at solving them within the framework of the context that produced them. This allows them to share the burden – of both defining and solving the problem – with the task environment as they respond directly to emerging issues. The adequacy of the solution they reach becomes apparent in relation to the role it must play in allowing activity to continue.”72 Bates mentions the examples somewhat like these and called them cooking problems. The examples are from the work of Lévi-Strauss and concern the seemingly deep principles that underlie cooking and eating of foods across cultures. Bates concludes by noting “that the universal facts reside in the structure of the cooking problem, and not in the environment per se. Such task structures … lie neither in the organism nor in the environment, but at some emergent level between the two.”73 The classic example would be the creation of the hexagonal structure of the honeycombs found in beehives. This almost perfect hexagonal structure need not depend on a kind of architectural intelligence, or innate geometrical instinct of the bees. Instead it is the inevitable outcome of the packing principle, the physical laws governing the behaviour of spheres being packed under pressure from all sides. “The bees ‘innate knowledge of hexagons’ need to consist of nothing more than a tendency to pack wax with their hemispherical heads from a wide variety of directions.”74 Could this perhaps be compared to for instance the operation of the market. No one needs to have much tacit nor explicit knowledge of the market. Market forces determine the result behind the back of the individual actors in a market. On the basis of these arguments might one dare suggest that an attempt to substitute the packing principle or the market would demand, in the case of the bees, that every bee be endowed with a sense of geometry, and ability to calculate even better than it already can (for instance when communicating the distance and direction to flowers to other bees of the hive), and in the case of the market that human beings be endowed with an extremely comprehensive knowledge of economic relations and fantastic calculating abilities in order to create a command economy that would outperform the market. This essay represents work from my book “ Beyoond rules in society and business” Edward Elgar 2002 & 2004 . Notes 1 DeLillo (1984/1986) p. 149. 2 Before attempting to show the importance of tacit knowledge it is important to emphasise that when we are talking about knowledge we are painting with a broad brush, partly taking for granted what is meant by knowledge. In order not to leave too much to interpretation a few hints may be necessary though. In common usage one might discern between “know about” or knowledge and “knowhow” or skill, in other words between Wissen and Können. Here we see Wissen and Können as different aspects of knowledge and include both meanings. Ryle discusses “knowing how” and “knowing why” and shows the differences and parallelism in small examples. We may forget how to tie a reef knot, and forget that the German word for knife is Messer (Ryle 1949). According to the German Duden dictionary “können” may be regarded as “erworbenes Vermögen, auf einem bestimmten Gebiet mit Sachverstand, Kunstfertigkeit o. Ä. Etwas [Besonderes] zu leisten: sportliches, handwerkliches … While “Wissen” includes “Gesamtheit der Kenntnisse” that someone has, but also “Kenntniss, das Wissen von etw.: ein wortloses, untrügliches Wissen” (Duden 1996). Bereiter and Scardamalia mention that to a cognitive psychologist, knowledge would be formal or declarative knowledge, while skills would represent procedural knowledge (Bereiter & Scardamalia 1993). In Philosophische Untersuchungen Wittgenstein writes: “Die Grammatik des Wortes ‘wissen’ ist offenbar eng verwandt der Grammatik der Worte ‘können’, ‘imstande sein’. Aber auch eng verwandt der des Wortes ‘verstehen’ (Eine Technik ‘ beherrschen’).” (Wittgenstein 1953) part I, p. 150. 3 The letters in “It is raining” do not contain enough information to understand the expression without prior knowledge. It seems to be just a kind of shorthand convention. To see this one only has to read the absurd conversation about whether it is raining or not in DeLillo’s White Noise, (DeLillo 1984/1986), pp. 22–25. 7 Reported in Holmes (1998), p. 35. 8 New Scientist (5 September 1998). 9 Wittgenstein (1976), p. 397. 12 Black (1990). 13 Dreyfus (1987), p. 51. See also the discussion in Dreyfus (1997) and in Bereiter & Scardamalia (1993). 14 Polanyi (1958/1962), p. 49. 15 I suddenly see that what I have written here is similar to a thought found in Wittgenstein’s later work: “Wer ein Blick für Familienähnlichkeiten hat, kann erkennen, daß zwei Leute mit einander verwandt sind, ohne sagen zu können, worin die Ähnlichkeit besteht…” Wittgenstein (1980), p. 97. 16 Russell & Fernández-Dols (1997a), p. 3. 17 Frijda & Tcherkassof (1997), pp. 85ff. Compare with Wittgenstein’s remarks in Wittgenstein (1980), passim. 18 Schön (1983), p. 54. 20 Josefson (1987), p. 27. 21 Ibid., p. 26. 22 Wittgenstein (1958), parts II/XI. 23 Beach et al. (1997), p. 33. 26 Quoted in Petersen (1997). 27 Ibid. 28 Ibid. 29 Ibid. 30 Quoted from interview made by members of CREDO in Jyske Bank A/S 1996. 31 Quoted from interview with the CEO of Jyske Bank A/S 1996. 34 Dennett (1991), p. 111. 35 Quoted in Dennett (1991), p. 258. 36 Hoffman (1998). 40 Bereiter & Scardamalia (1993), p. 62. 41 Fodor (1983), p. 88. 42 Polanyi (1967). 45 Polanyi (1967), p. 18. 46 Ibid., p. 18–19. 48 Expertise is discussed in a series of articles in Chi et al. (1988). 49 McCrone (1998). 50 Polanyi (1967), p. 20 51 Ibid., p. 36. 52 This is mentioned in Aitchison (1996), p. 12. 55 As an example of how individuals and community interact one may use the following: “When ants are looking for food, they walk to a certain distance from their nest, and then they go about randomly. When one of them finds food, it goes back to the nest, dispersing pheromones on its way. These pheromones attract other ants, which disperse more pheromones, and so on. In this manner, an organized ant-trail is formed, although no-one planned it in advance. It emerges from the collective behaviour of the individual ants. A significant point is that pheromones evaporate quickly, so that once the food is finished, the trail disappears. Perhaps we should learn from this how to let go of accepted institutions and modes of thinking once they have stopped serving their original purpose” (From an interview with C. Langton from the Santa Fe Institute found at http://www.santafe.edu/~cgl/). 56 A similar idea based on somewhat different arguments is presented by many cognitive scientists. Jackendorff argues that what happens in the brain is mostly unconscious. We only become aware of the result of the activities, or as Jackendorff would have it, computations. See for instance Jackendorff (1987) and Jackendorff (1994). 57 Polanyi (1967), p. xi. 58 Wittgenstein (1980), part II/49. 61 Collins (1990), p. 109. 62 Wittgenstein (1970), p. 351. 64 Results from a questionnaire used in Course 2 on Value-based leadership and management, Jyske bank A/S, 24. Silkeborg, November 1997. In a way they were saying in chorus, like the mob in Monty Python’s Life of Brian, “We are all individuals”. 65 Collins (1990), p. 109 66 James (1896/1987), p. 206. 68 Wittgenstein (1969), p. 15. See also Haller (1981), p. 65. 72 Brown et al. (1988), p. 14. 73 Bates (1984), p. 189. The is a topic that touches upon developmental psychology, as represented in the classical ideas of Waddington, Piaget and Vygotsky, and modern attempts as found in connectionist perspectives on development. See for instance Waddington (1957), Piaget (1952), Vygotsky (1978) and Elman et al. (1996). 74 Bates (1984), p. 189. |

Author

Verner C. Petersen Archives

May 2024

|