|

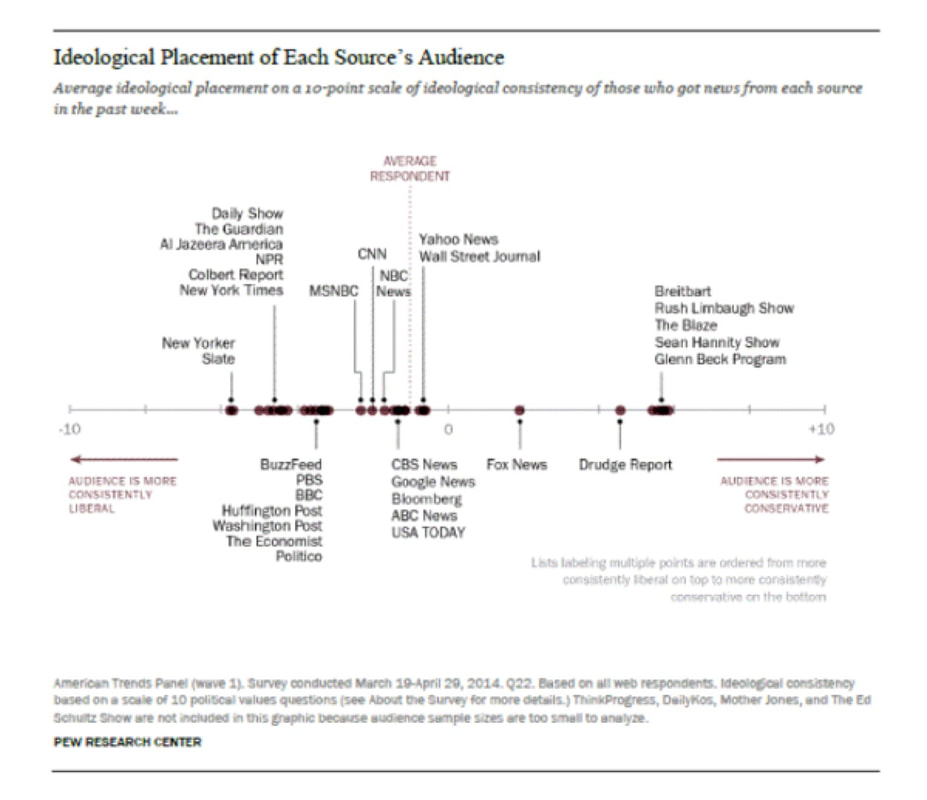

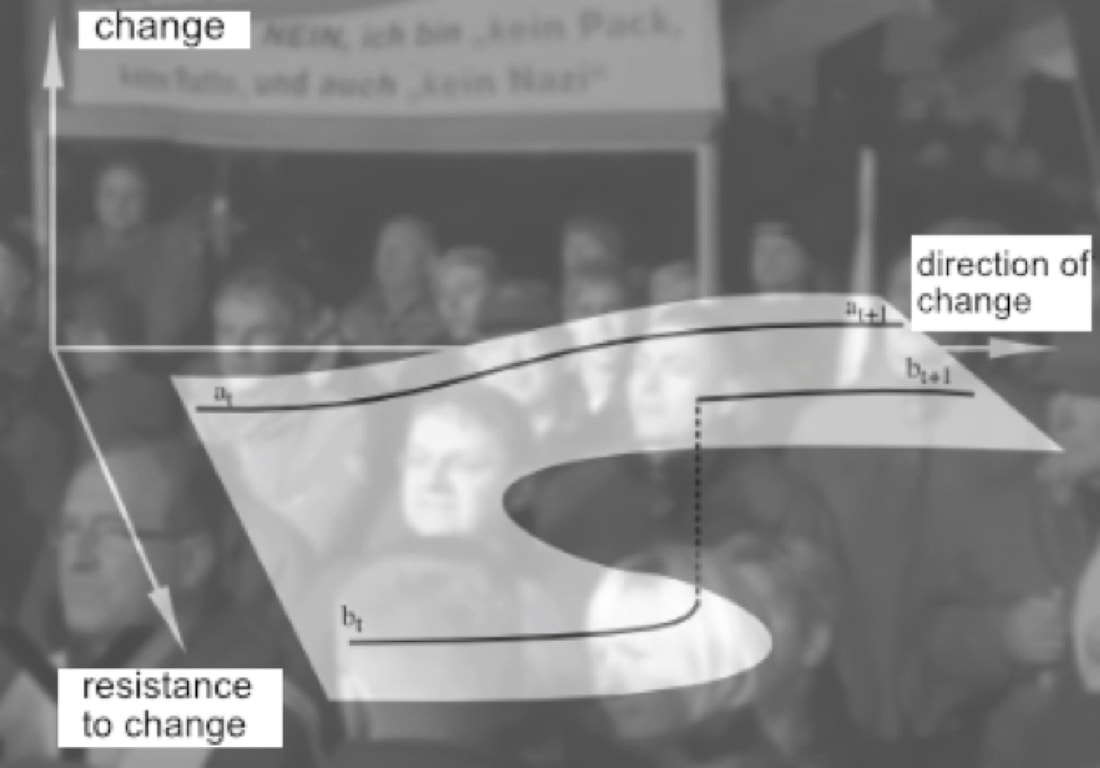

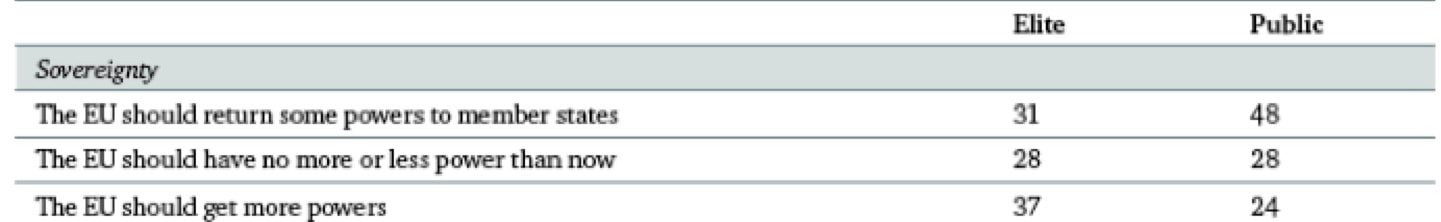

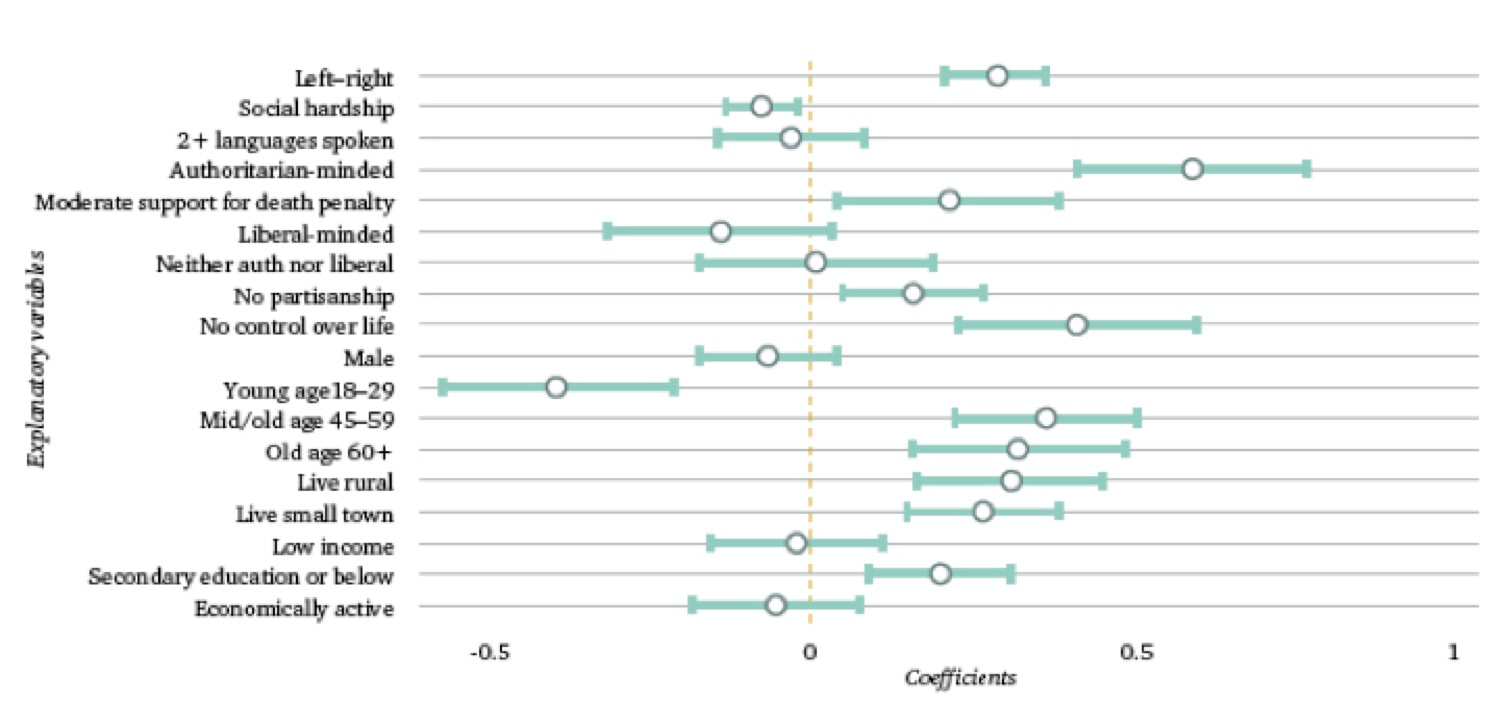

Revealing video clips leading to allegations of corruption Friday 17 July The German newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung and the magazine, Der Spiegel, publishes clips from a video that must have come from a sting operation. The video was apparently recorded with several hidden cameras on 24 July 2017 in a house on Ibiza and show Hans Christian Strache of the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), later Vice-Chancellor in the Kurz Government, and Johan Gudenus, also a member the FPÖ, in animated conversation with an unseen women, apparently posing as a niece of a Russian oligarch. She tells the group in the room that she wants to invest 250 millions Euro in Austria, money that may not be entirely legal. What can the FPÖ offer her? This is where it gets interesting. The seemingly rather intoxicated FPÖ members discuss casino licenses, the sale of an old luxury hotel, contracts for highway construction -- all of it for the Russian investor. They even discuss a takeover of the Kronen Zeitung, one of Austria's most widely circulated newspapers." (Der Spiegel). Strache really goes out on a limp with his suggestions for what the FPÖ could do when in government and how that could benefit the Russian investor: "Das Erste in einer Regierungsbeteiligung, was ich heute zusagen kann, ist: Der Haselsteiner (Chef der Strabag [large construction company]) kriegt keine Aufträge mehr. (…) Dann soll sie nämlich eine Firma wie die Strabag gründen, weil alle staatlichen Aufträge, die jetzt die Strabag kriegt, kriegt sie dann.“ (news.at). The Russian investor might also buy the large Austrian paper "Kronen Zeitung" and promote the interests of the FPÖ: "Wenn sie die Kronen Zeitung übernimmt drei Wochen vor der Wahl und uns zum Platz eins bringt, dann können wir über alles reden." (Kronen Zeitung). There is talk of ways to support the FPÖ with money and how it could be secretly delivered, hidden from prying eyes. In what is perhaps the most bizarre part of the short clips published from a 7 hour video Strache talks about secretly getting compromising material on political opponents and having it published by someone else, thus hiding its origin. Precisely what is happening to him at that moment. At some point Strache may have thought that this is too good to be true, and whispers that it must be a trap, but his companion assures him it isn’t: "Falle, Falle, eine eingefädelte Falle", soll er Gudenus zugeflüstert haben. Dieser habe indes gesagt: "Des is ka Falle." (Kleine Zeitung). When the video clips were published Strache insisted that he had several times insisted that everything must be legal, although some of his suggestions certainly do not sound legal. Sueddeutsche Zeitung und Der Spiegel admit that the source of the video is known but they will not reveal it. But rumours begin to pop up here and there about a dubious lawyer and some sort of private eye that may have been involved in the operation. Interesting questions thus remain Who arranged the sting operation with what purpose? Why was it published now a few days before the election to the European Parliament? Was is responsible and legally okay for Sueddeutsche and Der Spiegel to publish clips from a video that evidently was made secretly and presumably illegally, of a private meeting showing intoxicated politicians promising all sorts of things? What might be the reason for giving the material to a German newspaper and magazine and not Austrian newspapers? Neither Sueddeutsche nor Der Spiegel is making a secret out of their continuing efforts to reveal what they see as the problematic nature of right wing populism, in their defence of democracy. Der Spiegel: "Demokratien sterben heute kaum noch durch gewalttätige Systemveränderungen - sie werden von innen ausgehöhlt. Um das zu verhindern, müssen sich alle demokratischen Kräfte zusammentun" (Der Spiegel). The turquoise-blue coalition government under Chancellor Kurz was eyed with distrust and aversion when it came about in 2017. Der Spiegel: "In Österreich regieren ab heute Rechtspopulisten mit, darunter Politiker mit rechtsextremer Vergangenheit und Verbindungen in die Neonaziszene. Das birgt Gefahren - und erfordert Kritik." (Der Spiegel). Perhaps it is worth mentioning that Der Spiegel has just concluded an investigation into a scandal in their own backyard. A journalist who published 55 articles in the magazine based upon made up interviews and false statements. Why wasn't the video published in 2017? It was made a few month before the 15 October 2017 elections in Austria, when Kurz's Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) came first and the FPÖ third, thus leading to the turquoise-blue coalition government of the two parties under chancellor Sebastian Kurz. Presumably its publication then would have ruined FPÖ's chances of getting into government and thus prevented Kurz from becoming Chancellor. Did the purpose of the sting operation perhaps change during the two years, from a kind of revenge, or blackmail, to political defamation, or....? Does the seven hour long video contain more explosive material, as those who organised the sting operation apparently had put cameras and microphones everywhere? The effect on Austrian ands perhaps even European politics The day after the publication of the video clips Strache announced that he was laying down all his political offices and party functions. He excused his embarrassing behaviour: "In einem siebenstündigen privaten Gespräch in meinem Urlaub wurde ich – ja, unter Ausnutzung einer zunehmenden Alkoholisierung, ja, es war eine besoffene Geschichte, und ich war in einer intimen Atmosphäre – verleitet, auch unreflektiert und mit lockerer Zunge über alles und jedes zu polemisieren. Und ja, meine Äußerungen waren nüchtern gesehen katastrophal und ausgesprochen peinlich." He still insisted that he hadn't done anything illegal, and that nothing had come of the meeting. But he also attacked those behind the video and its publication. "Genug ist genug" Chancellor Kurz apparently wanted to act just as quickly, but before he did that he wanted to dismiss the interior minister, Herbert Kickl, the outspoken hardliner from the FPÖ, as Kurz didn't want him to be responsible for a thorough investigation into the affaire. Kickl wouldn't leave and the FPÖ wouldn't accept his dismissal, threatening to leave the government if Kickl was dismissed. On the evening of Saturday 18 May Kurz had made up his mind. "Genug ist Genug." He said he had known that it would not be easy to work with the FPÖ and had swallowed some of the problematic incidences and scandals brought about by members of the FPÖ, but this was way too much and as the FPÖ would not accept his dismissal of Kickl, he saw no other way than to call for re-election as soon as possible and in meantime place experts and technocrats in the offices occupied by FPÖ ministers. Soon after the FPÖ threatened Kurz with a no-confidence vote together with some of the other parties. The small "Jetzt-Liste Pilz" party with eight sets in the "Nationalrat" jumped at the chance to unseat Kurz: "Die oppositionelle Liste „Jetzt“ kündigte für die nächste Nationalratssitzung – deren Termin noch nicht feststeht - einen Misstrauensantrag gegen den Kanzler an." When this will take place is unknown and so is the outcome, meaning that at the moment we don't know if Chancellor Kurz will have to step down as a result of the Ibiza video affair. It will presumable depend on the social democratic party's (SPÖ) stance. Sunday 19 May Bundespräsident Van der Bellen, announced that re-election would take place as soon as possible in September. "Ich plädiere für NewWahlen im September, zu Beginn des Septembers“ (Van der Bellen). The first opinion poll, already shows a here and now effect of the video and the talk about it: Kurz's party, the ÖVP wins 4 per cent and stands at 38 per cent, while the party of Strache's FPÖ goes from 23 percent to 18 per cent. Not a sensational loss at the moment. Opinion is divided on the need for the re-election. 60 percent are in favour while 40 per cent are against. Europe-wide consequences? The Ibiza video may have consequences for right wing protest parties, or so-called populist parties all over Europe. It speculated that it may create distrust against these parties, thus leading to less success in the European Parliament elections and accordingly less representation in European Parliament. The Ibiza-gate might lead people to believe that such abominable behaviour is characteristic of all these parties. Perhaps this may explain part of the reason for the sting operation. "Die Videoaffäre hat Auswirkungen weit über Österreich hinaus. Denn nur eine Woche vor der Europawahl macht die Affäre deutlich, wie dierechtspopulistische FPÖ demokratische und rechtsstaatliche Prinzipien ignoriert, wenn sie mitregiert. FPÖ-Chef Strache zeigt sich im Video nicht nur bereit zur Korruption und zur engen Kooperation mit zwielichtigen russischen Partnern. Auch die Pressefreiheit interessiert ihn nicht, für ihn positive Inhalte in der mächtigen „Kronen Zeitung“ will er sich erkaufen. Viele Wähler dürften bei der FPÖ ein rechtspopulistisches Muster erkennen, das sich auf den französischen Front National oder die deutsche AfD übertragen lässt." (RP). Not a singularity, but a universal characteristic Can Strache's and Gudenus' behaviour in the video be seen as a singularity, as a one off event, that may show the lengths individuals like Christian Strache and Johan Gudenus would be willing to go to in order to achieve and maintain power, especially if it can be done in what they must surely believe is secrecy? Or can the behaviour in the video be seen as a universal characteristic of what is often called far right populist parties? The German foreign minister, Heiko Maas, from the SPD is not in doubt. Right wing populist are enemies of freedom and joining them is irresponsible. "Rechtspopulisten sind die Feinde der Freiheit. Mit Rechtspopulisten gemeinsame Sache zu machen, ist verantwortungslos." (Bild am Sonntag). Although Maas believes that people in Europe are aware of this, one must act against these parties. Merkel, who seems to spend lot of her slow departure from the chancellorship outside Germany, is of a similar opinion. In Zagreb she said that the populist trends despise European values and wants to destroy them. We must act decisively against that. "Wir haben es mit Strömungen, populistischen Strömungen zu tun, die in viel Bereichen diese Werte verachten, die das Europa unserer Werte zerstören wollen. Dem müssen wir uns entschieden entgegenstellen." Others talk of the moral rot, corruption and dangerousness of right wing populism in general. The general opinion especially in Germany seems to that the Ibiza video exposes a universal characteristic of those despicable far right parties. The righteous against the far right Does that mean that the righteous people have been right to abhor right wing populist parties and the people who vote for them? That right wing protest parties and followers really are deplorables. Completely unacceptable and thus deserving the strongest possible condemnation. The term deplorable was used by Hillary Clinton to characterise supporters of Donald Trump. During a LGBT fund raising campaign on September 9 2016, standing behind a lectern with the slogan “Stronger Together," she said: “You know, to just be grossly generalistic, you could put half of Trump's supporters into what I call the basket of deplorables. Right? They're racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic – Islamophobic – you name it." (Time). Around the same time the then German foreign minister Sigmar Gabriel put the upcoming right wing party, the AfD, into a corner with Nazis saying: "Alles, was die erzählen, habe ich schon gehört – im Zweifel von meinem eigenen Vater, der bis zum letzten Atemzug ein Nazi war." (Die Welt). Already in 1999 the Danish prime minister at the time, Poul Nyrup Rasmussen, compared the Danish People's Party to a pet that would never be house trained: "Derfor siger jeg til Dansk Folkeparti: Uanset, hvor mange anstrengelser, man gør sig - set med mine øjne – stuerene, det bliver I aldrig!" (Folketinget) To the self-proclaimed righteous parties, media and people, the right wing protest parties and their followers in Europe really seem to be deplorables, that deserve intense critical scrutiny, using all possible means. Whenever something deplorable is discovered, like the Ibiza video, it is seen as evidence of depraved values of these parties and their supporters. A few warning voices are heard. For the former chief of the German "Verfassungsschutz" who recently had to go after criticising Chancellor Merkel, the sting operation is breaking a taboo: "Derartige Fallen zu stellen, ist mitunter einfach und kann auch zum Instrumentarium des Dirty-Campaigning gezählt werden, bei dem versucht wird, den politischen Gegner mit teilweise geheimdienstlichen Mitteln zu diskreditieren." (freiewelt.net). Others have voiced the same concerns, and want to see who has been behind the sting operation. When similar cases are seen as singularities In 2000 the former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl from the conservative CDU party admitted that he had for years received millions in illegal donations and hidden them in so-called "Schwarze Kassen" or black accounts, without declaring them in the party's books. He was accused and then acquitted, even though he refused to name the donors, arguing that he had given them his word. Wolfgang Schäuble, the former German finance minister from the CDU and now highly respected Bundestagspräsident, was involved in the so-called "Spenden affäre" He admitted in 2000 to have received an envelope containing 100.000 DM in cash from a dubious weapons dealer. "Schäuble [hatte] am 10. Januar 2000 eingeräumt, vom Waffenhändler Karlheinz Schreiber im Jahre 1994 eine Bar-Spende über 100.000 DM für die CDU entgegengenommen zu haben." Did this lead to condemnation of the whole of the CDU party? Not really, it was mostly seen as embarrassing singular activities of Kohl and Schäuble and they were ostracised for some time. A sting operation set up by journalists revealed three peers from the House of Lords as being involved in corruption. "A Sunday Times reporter posed as a lobbyist from a solar energy firm; the three politicians allegedly agreed to use their influence to push the firm’s agenda in return for monthly payments of up to $18,000" (OCCRP) The two peers from the labour party were suspended, while the third peer fro the Ulster Unionists gave up his position. Now, did the German cases or the English sting operation that certainly had some similarity with the Ibiza video lead to condemnation of the respective parties of those involved? Was it seen as a universal characteristic of the respective parties and their members? No, the revelations certainly didn't fall back on people voting for the party. Mostly it was in fact seen as singularities, although there have been some procedural changes in the involved parties in order to avoid similar embarrassments in the future. Why this difference in view between established parties and protest parties caught in the act? In the case of right wing protest parties incidences like the Ibiza video appear to taint the whole movement. If one black case is found it paints the whole, movement black in the eyes of the righteous. It just confirms what they had thought all along. If similar incidences are found among established parties, that are seen as belonging to the righteous side, the involved may be ostracised, but it doesn’t really taint the rest of the party, and doesn't paint them all black in the eyes of the righteous. In curiously parallel to the view asserting that self confessed Muslims committing atrocities are singularities, not representative of the majority of Muslims. Shining the light on the deplorables – the role of the media Why is does incidences among right wing parties taint everything they and their supporters do, while other parties avoid having the whole movement coloured black? What is role of the media, who may be involved in sting operations and revelations of misconduct, and who are our primary source of information about the incidents and opinions about such incidents? Could it be that established media in general are especially critical in their treatment of the right wing protest parties and movements? Even in the way they are talking about them, often using derogatory terms like populist, far right, extremist, bigot, fremdenfeindlich or xenophobic, rechtsradikal, pak, homephobic, islamophobic, nazist etc. Are the established media in general neutral in their treatment of the subjects they choose to take up, and in their reporting? Or do they have certain ideological and political bias in what is taken up and the way they report? Not an easy question to answer decisively. But there are indications we may use. Studies in Germany show that the heart of German journalist beats left. A study from Freie Universität Berlin shows how journalists see themselves. 26,9 per cent felt close to the Green Party, 15,5 close to the social democratic SPD, 4,2 per cent to the left party (Die Linke), while 9 per cent felt close to the conservative Christian Democratic parties CDU/CSU, and 7,4 per close to the liberal FDP. A majority of journalists were thus leaning left. Another study asking journalists for their basic belief showed that 48 per cent felt they belonged on the left side, 17 per cent felt they belonged to right side and 15 per cent to the middle. In a US study of financial journalists, whom one might suppose to have conservative and libertarian views, turned to show that they were mostly leaning left, with 58 per cent seeing them selves as leaning left of centre. (investors.com). A study from PEW research from 2014 show the ideological placement of readers and views of US media sources. (PEW Research 2014) Indirectly this might be seen as confirming the left bias of some of the most widely used media sources. Although I suspect that readers and viewers on both sides may insist that they have the most objective sources. The strange irony is that in many cases the left leaning media are owned by people and organisations that no one would regard as left leaning. Perhaps what we have is a self-confirming and according to view, vicious or a virtues spiral, whereby the righteous established parties and left leaning media confirm each other's views, especially in their shared disgust and eagerness to demonstrate the deplorability of right wing protest and populism We suspect that all this means that we cannot really expect an unbiased view of the existing or emerging right wing protest parties. Is this a problem? Causes for disgust Perhaps there is good cause for the critical view of right wing protest parties and movements. Protest parties as per definition represent people standing against the establishment, which may make them attract unsavoury characters. Not yet being established, these parties may be seen as an outlet for these characters' own personal frustrations and problems. This may lead to outcries and outbursts of activity that put the whole movement in disrepute. It is not only a question of protest actions and problematic incidences though. It is also about the verbal outbursts. To what we have called the chattering classes, consisting not necessarily of those in power, but of all those whose views are represented in the media, expressions used by the "unwashed deplorables " may seem extraordinarily bigot, racist and generally obnoxious. We are not talking about people in power, they may exerts their power and influence in private, just the chattering classes, with self-proclaimed progressive and politically correct views It is a question of the difference between those who may seethe with frustration, but unable to give voice to sophisticated expressions of their frustrations, and the chattering classes, who are characterised by their ability to express themselves in well-formed opinions, terms and phrases. Thus language and forms of expression are something that lead to divisiveness in society, not something holding it together. Perhaps Bernie Sanders has understood that, when he said: "I come from the white working class, and I am deeply humiliated that the Democratic Party cannot talk to the people where I came from." Strangely, this is what Trump can. On the one hand we have the unarticulated roar of protest, and on the other hand the sophisticated words of rejection. Except of course for some politicians using terms like racist, bigots, deplorable, Nazi etc. about the deplorables. Almost mirroring the other side, but being on the righteous side, they are of course seen as justified in using characterisations that would seem to preclude all chances of dialogue with their opponents Perhaps these differences are unavoidable consequences of movements in the making. Looking back at the history of revolutions, this would seem happen when hereto suppressed frustrations and problems from the bottom of society pop up as it were to the surface. Like foul and evil smelling gases from the bottom of a murky lake. If this is how it is viewed by established parties, media and all self-confirmed righteous opinions, then it is no wonder that they hold their noses and turn away in disgust. Trying to silence the "deplorables" is deplorable Instead of listening and attempting to understand the reasons for protest it would seem that the righteous are mostly occupied with shining a harsh light on the protest parties and their followers, while keeping themselves in the dark, in order to find something confirming their prejudgements, and defaming the protesters. Finding some sort of Russian connection, illegal donations, misuse of donations, members and supporters with dubious backgrounds or behaviour, and politically incorrect and offending language. Ignoring that there may be real and relevant causes for the protest. In earlier blog post like the "The yells of protest from the inarticulate middle" and "Ominous signs of seismic activity in the political landscape" we looked the explanations for protest parties growing in importance in several countries. What might then be the common causes for some of the tremors that are felt all over the Western world? We see a growing divide between a kind of self-appointed elite and the rest of society. One side of the divide consisting of a real power elite and a chattering class proclaiming a progressive and liberal view, and consisting of people with the political correct view, even though they might split into a variety of identity movements. On the other side of the divide we find both people with a more burkian (from Edmind Burke) conservative view, and those who are seen as left-behind, "the deplorables." We may find some support for our view in a curious study published by Chatham House, "The Future of Europe – Comparing Public and Elite Attitudes." The study seems to find a similar binary split in society. Protest movements vital to democracy Those who hold their noses and shut their eyes to the protest today seem to have forgotten Mill's sensible advice in his chapter "on the liberty of thought and discussion: "When there are persons to be found, who form an exception to the apparent unanimity of the world on any subject, even if the world is in the right, it is always probable that dissentients have something worth hearing to say for themselves, and that truth would lose something by their silence." In a way the right wing protests derided as populism may represent something that is vital to democracies. The ability to change themselves, in fits and starts, through trial and error, when developments have created inequality, division, too great distance between the those in power and those who are not, mismatch between economic and technological development and social conditions. Something that isn't possible in other kinds of regimes, whether authoritarian, so-called socialist regimes, or faith based regimes. The protests may have both positive effects and negative effects, but the important thing is that they represent something that is important to large sections of the populace, not to be ignored and derided by a snapchattering classes of politicians, media, and the self-proclaimed righteous. To Kaltwasser (what an appropiate name) populism is both a necessary corrective and threat: Positive effects Populism can give voice to groups that do not feel represented by the elites, by putting topics relevant to the ‘silent majority’ Populism can mobilise excluded sections of society, improving their political integration Populism can represent excluded sections of society by implementing policies that they prefer Populism can provide an ideological bridge that supports the building of important social and political coalitions, often across class lines Populism can increase democratic accountability, by making issues and policies part of the political realm Populism can bring back the conflictive dimension of politics (‘democratisation of democracy’) Negative effects Populism can use the notion and praxis of popular sovereignty to contravene the ‘check and balances’ Populism can use the notion and praxis of majority rule to circumvent minority rights Populism can promote the establishment of a new political cleavage, which impedes the formation of stable political coalitions Populism can lead to a moralisation of politics, making consensus extremely difficult (if not impossible) Populism can foster a plebiscitary transformation of politics, which undermines the legitimacy of political institutions and unelected bodies Ironically, by advocating an opening up of political life to non-elites, populism can easily promote a shrinkage of ‘the political’ Smooth change or abrupt break in unruly times? Elsewhere we have speculated on ways in which protest parties and movements might influence democracy and society. We see two very different outcomes depending on the amount of resistance to protest parties and movements. On the one hand an almost smooth and gliding incorporation of protest views in mainstream ideology, politics and political decision-making. On the other hand an abrupt break that may represent almost revolutionary break. A break that might be saving democracy or destroying it. The difference can be illustrated with a kind of carpet fold model. At one end the fold is smooth and almost imperceptible, signifying little resistance to move from time a(t) to time a(t+1). At the other end the fold is abrupt and no smooth transition can take place, instead we have an abrupt change from time b(t) to b(t+1) thus representing some kind of revolution. An example of smooth change may be found in Denmark in the quiet way the views of the right wing Danish Peoples Party became incorporated in mainstream politics. Prompting other parties to more or less perceptible changes in the views, and making them lean into the space created by The Danish Peoples Party, today to such a degree that they may have taken the wind out of the sails of the Peoples Party.